The original Ford Fiesta, introduced in 1976, was the Ford Motor Company’s most important new car of the seventies. It was a staggeringly expensive project that began Ford’s conversion to front-wheel drive and took the company into the modern B-segment for the first time. However, the Fiesta also provoked great internal controversy and emerged only after a protracted and contentious development period. In this installment of Ate Up With Motor, we look at the origins and history of the 1976–1983 Mk1 Fiesta, the Fiesta XR2 hot hatch, and the 1984–1989 Mk2 Fiesta.

FORD THINKS SMALLER

Perhaps the most remarkable and ironic thing about the original Fiesta is that while it was an extremely important car for Ford, quite a few people within the company didn’t want to build it at all. In size, technology, and market, the Fiesta took Ford into new territory into which some senior executives weren’t convinced the company even needed to venture.

In the late sixties, Ford’s European operations were generally doing well. Most models were either new or about to be refreshed and the much-publicized racing program had boosted Ford’s image. The corporation’s previously separate and competitive British and German subsidiaries were being integrated, which would shortly result in a unified model line-up, and Ford was preparing to launch the new Capri, a European answer to popular American pony cars like the Mustang.

Despite that success, by 1969 a few voices within the company were cautiously suggesting that Ford needed something more: a smaller subcompact car for the burgeoning B-segment. While Ford was selling well in Great Britain and industrialized, relatively affluent countries like West Germany and Belgium, central and southern Europe were another matter. For many Italians, for example, modest wages, high fuel prices, and restrictive vehicle taxes made even C-segment cars like Ford’s new Escort an expensive proposition. All Ford could offer such buyers was a slightly cheaper Escort with an underpowered 940 cc (57 cu. in.) version of the familiar four-cylinder Kent engine. As a result, Ford’s market penetration in those regions was limited and sales of rivals’ smaller B-segment models were growing.

A 1969 Ford Escort 1100 De Luxe. (Photo: “Ford Escort Mk I 2012-07-15 13-39-21 1 1 2 fused” © 2012 Berthold Werner; resized 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

Surprisingly, Ford management didn’t initially consider that a serious problem. Ford’s Marketing staff insisted that the B-segment was a transitory phenomenon that would gradually shrink and all but vanish within a decade or so. For Ford to enter that market, they argued, would be a needless waste of resources. (Throughout the seventies, there was on-again, off-again talk of Ford developing a cheap microcar for emerging markets, but such a car probably wouldn’t have been offered in Europe or North America.)

Predictably, Finance was even more opposed to the idea of Ford developing a B-segment car. Finance’s objections echoed those that been levied against virtually every small car any U.S-based automaker had ever contemplated: that a smaller car would not be much cheaper to design or manufacture than the Escort (which had already been cost-engineered to within an inch of its life), would have to be priced lower (cutting into profit margins), and, if sold in meaningful numbers, would cannibalize sales of the company’s bigger, more profitable cars.

After considerable argument, Ford of Britain’s vice president of product planning, Ralph Peters, established a small task force to study the issue and create a proposal. A year later, the team presented their findings and a fiberglass mockup to the corporate Product Committee, arguing that Ford could sell 300,000 B-segment cars a year, most of them to customers who had never previously bought a Ford — or perhaps any new car — before.

Those projections didn’t end the skepticism, but they did provide the B-car idea a new credibility. Even the most reactionary or penurious executive can hardly ignore potential business of that scale, especially if it offers the possibility of significantly increasing market penetration. The latter had been a particular sticking point for Ford in the U.S.; for all the company’s success in product development, Ford’s domestic market share had remained frustratingly static.

While adding an extra quarter million or more sales a year sounded good, building so many additional cars would entail a major expansion of Ford’s European production capacity and mean considerable financial risk. If the product bombed or if Marketing’s predictions about the half-life of the B-segment turned out to be correct, the whole exercise would cost Ford dearly: at least $700 million.

THE FRONT-WHEEL-DRIVE CONTROVERSY

Other European automakers, particularly in France and Italy, had fewer qualms, and the late sixties and early seventies saw an explosion of new small cars. Early salvos included the Simca 1204 and Autobianchi A112, followed in the spring of 1971 by the A112’s cousin, the Fiat 127. By the end of 1972, these were joined by the Renault 5, Peugeot 104, and Honda Civic.

The Mk1 Fiesta’s original target: the early Fiat 127. (Photo: “Fiat 127 green” © 2009 Thomas doerfer; resized 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

By the time the Civic bowed, Henry Ford II had reluctantly conceded that Ford needed a B-segment car for the European market. The abundance of new entries in that segment meant that Ford had a simple choice: They could join the party and grow or sit back and lose market share.

Nonetheless, there was still considerable disagreement about what format a smaller Ford should have. Previously, small cars had used a variety of mechanical layouts, but by 1972, a new orthodoxy was emerging: transverse front engine, front-wheel drive, space-efficient suspension, and a two-box shape, eventually including a rear hatchback for greater load-carrying versatility. All but the last had been seen more than a decade earlier on the BMC Mini, but it was not until the seventies that the front-engine/front-drive (FF) hatchback became the norm in this class. (Some competitors, including Fiat and Peugeot, initially did without the rear hatch, but the market quickly demonstrated a strong preference for the three- or five-door layout.)

Today, the choice seems obvious; the packaging advantages of the FF layout are hard to ignore even for larger C-segment cars, much less smaller ones. However, in the early seventies, Ford’s Finance staff still vigorously opposed any talk of front-wheel drive. They hadn’t forgotten Ford’s cost analysis of the early Mini, which had concluded that BMC was selling each car at a substantial loss.

The Mk1 Fiesta is sometimes described — incorrectly — as Ford’s first FWD production car, but that honor actually goes to the 1963–1966 Taunus 12M (P4). This is a 1965 Taunus 12M. (Photo: “Ford Taunus P4 12m BW 1” © 2008 Berthold Werner; released into the public domain by the photographer, resized and modified (obscured bystander faces) 2013 by Aaron Severson)

Ford’s own experience with front-wheel drive had been less than reassuring. Discounting an abortive early-sixties program to develop a front-wheel-drive Thunderbird, Ford’s only FWD models to date had been the German Ford Taunus P4 and P6 (sold as the Taunus 12M and 15M). Developed in Dearborn as the Cardinal, the P4 was originally intended for both the U.S. and Ford’s German subsidiary, but Lee Iacocca, then Ford Division general manager, had persuaded Henry Ford II to cancel the U.S. car at the last minute, leaving only the German version. The Taunus P4 and subsequent P6 weren’t a complete sales disaster, selling some 1.3 million units between 1962 and 1970, but they were expensive to build, cost more than most direct rivals, and were somewhat disappointing in both performance and market penetration. Few in Dearborn were eager to go down that road again, which is why the P6’s replacement, the Taunus TC, had reverted to rear-wheel drive. A few German engineers were disappointed, but Ford’s accountants no doubt breathed sighs of relief.

Ford’s thinking on small cars in this era was exemplified by the Escort, introduced in 1968 as Ford’s first Anglo-German passenger car. Developed to replace the British Ford Anglia 105E, the Mk1 Escort was at the smaller end of the C-segment, being considerably bigger than a Mini or a Fiat 600, but some 5 inches (127 mm) shorter than an Opel Kadett. Other than its size, the Escort was a thoroughly conservative design, with MacPherson strut front suspension; rear-wheel drive; a live axle on semi-elliptical leaf springs; and several variations of Ford of Britain’s trusty OHV “Kent” four, usually linked to a four-speed gearbox.

One of the various sporty spinoffs of the Mk1 Escort was the RS1600. Built at Ford Advanced Vehicle Operations in Ockendon, Essex, it used a special reinforced “Type 49” bodyshell and a 1,601cc (98 cu. in.) Cosworth BDA engine with belt-driven dual overhead cams and 115 PS DIN (85 kW). Naturally, the RS1600 was substantially more expensive than a “cooking” Escort. (Photo: “1971 Ford Mk I Escort RS1600” © 2012 Sicnag; resized and modified (reduced glare, obscured numberplates and some background details) 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, with this modified version offered under the same license)

To keep production costs and starting prices to a minimum, the Escort’s basic specification was basic indeed; standard were 12-inch wheels, drum brakes, and interior furnishings that only a determined skinflint or tightfisted fleet manager could love. Buyers could upgrade both the ambiance and the performance by choosing from a multitude of trim levels and option packs, while enthusiasts and automotive journalists were appeased with a selection of limited-production Twin Cam and RS models. The latter offerings in turn served to homologate those cars for rally competition, in which the Escort proved extremely successful.

It would be easy to scoff at this merchandising strategy, which Ford employed to varying degrees on most of its European offerings of the period, but it was an effective one (Ford sold more than 1.9 million Mk1 Escorts through 1974) and likely very profitable, which left Ford understandably reluctant to step away from it. While some senior executives — including Hal Sperlich, whom Lee Iacocca (now Ford president) had appointed to oversee the project as Iacocca’s special assistant — recognized the need for FWD, others still needed to be convinced.

PROJECT BOBCAT

In mid-1972, a new product planning and research team headed by Hal Sperlich, with Alex Trotman in charge of planning and Don DeLaRossa overseeing styling, began developing mockups of various FWD and RWD B-segment cars. Inevitably, a major focus of the project, which received the official codename “Bobcat” in October, was cost analysis. The goal was to undercut the price of the Escort by at least $100, something that promised to be a tall order.

Another early Fiesta rival: the Peugeot 104, seen here in SL Sport trim. (Photo: “Peugeot 104 SL Sport 2012-09-01 14-44-12” © 2012 Berthold Werner; resized 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

Since the hugely successful launch of the Mustang, Ford had put great stock in market research, so the Bobcat project went through several rounds of consumer marketing clinics. The results convinced the development team that the potential market was even bigger than they’d thought — their sales projections rose to more than 450,000 units a year, two-thirds of which were expected to be to first-time Ford customers — and that front-wheel drive, though expensive, was the only way to go. A RWD alternative called Cheetah (based on a cut-down RWD Escort) fared poorly with clinic participants.

Meanwhile, Ford was pondering the production question. Henry Ford II had already committed to building a new transmission factory in France and Ford executives had made overtures to General Francisco Franco’s ministry of industry and economic planning about opening production in Spain. The latter was a challenge; under Franco, Spain was a staunchly protectionist market. The dominant automotive players in Spain at the time were Renault and SEAT (Sociedad Española de Automoviles de Turismo), then controlled by FIAT, which were among the few companies able to meet Spain’s stringent 95% local content requirement.

In 1972, Ford convinced the Franco government to relax some of those requirements and allow Ford to build a new factory complex in Almusafes, near Valencia, which would eventually have capacity for 280,000 cars and 400,000 engines a year. Ford established a Spanish subsidiary in the fall of 1973, about three months after opening its new transmission plant in Bordeaux. Groundbreaking for the Almusafes facility followed in early 1974.

One of the various design studies for the Bobcat. (Image: Ford Motor Company)

The Bobcat did not yet have a clear styling direction; the mockups the development team had been using for cost analysis and consumer clinics were intended to define the basic package rather than establish any particular look or design theme. Iacocca, always keen to have multiple options, ordered a three-way contest between Ford’s design studios in Dunton (then led by Jack Telnack) and Merkenich (headed by Uwe Bahnsen) and the designers at Ghia, in which Ford had recently acquired a majority stake. The whole process was overseen by Ford of Europe design VP Joe Oros, the one-time George Walker associate whom Ford fans will recall was responsible for (among other things) the rocket exhaust taillights that were a signature feature of most U.S. Fords until the mid-sixties.

The winning design, approved in the fall of 1973, appears to have been based primarily on a design study by Ghia chief stylist Tom Tjaarda (in profile, the resemblance is hard to miss), although the finished product amalgamated elements of all three studios’ work. The design would not be finalized until late 1975 and would receive various additional tweaks, some driven by wind tunnel testing — still not common practice at Ford in those days.

According to Iacocca, even at this stage, there was still considerable reticence about actually producing the Bobcat. The project had some compelling points, chief among them the prospect of building cars in Spain, but the Bobcat represented the largest single product investment Ford had ever made. Finance remained dead-set against it, and Sperlich believed the same was true of Philip Caldwell, who became president of Ford of Europe in 1972. Caldwell’s successor, Bill Bourke, had a more favorable attitude, in part because of the OPEC oil embargo that began in late 1973, but the doubters and dissenters were not yet silenced.

Another Bobcat rendering, this one quite close to the finished product. (Image: Ford Motor Company)

Despite those reservations, the board of directors gave formal approval for the project in December 1973. The start of pilot production was set for mid-1976.

THE BOBCAT BECOMES THE FIESTA

Over the previous decade and a half, the Ford Motor Company had displayed a knack for identifying or creating new niches, but this time, Ford was leaping somewhat late into an increasingly crowded market. With so much at stake, the company was in no mood to take chances.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that the Bobcat emerged as a very conventional small FWD car. The only really unusual mechanical feature Ford considered, a novel type of torsion bar front suspension, was discarded in mid-1974 as too risky for production. The Bobcat was hardly a copy of any of its principal targets — which initially included the Fiat 127 and later the new Volkswagen Polo and Audi 50 — but there was nothing about it that would have seemed out of place on the spec sheets of its competitors.

Nonetheless, the Bobcat scored well in marketing clinics against those rivals. Ford officials were similarly pleased with the prototypes, early drivable examples of which were completed in the fall of 1974. There were various minor changes throughout 1974 and 1975, many stemming from the ongoing struggle to find the right balance between cost and content.

GM’s Oldsmobile Division used the name “Fiesta” for some of its station wagons (estates) in the late fifties and early sixties. This is a 1957 Oldsmobile Super 88 Fiesta. (Author photo)

One of the ongoing questions about the Bobcat was what to call the production car. Ford could conceivably have called it Bobcat, but the company was already using that name for Mercury’s version of the compact Pinto, which would have presented problems if the new car was to be sold in the U.S. market. After considering and rejecting a lengthy list of possible names, including Bravo, Amigo, Metro, and Sierra, Henry Ford II chose Fiesta and convinced General Motors chairman Tom Murphy to release the name, which GM owned, but hadn’t actually used in some years.

If GM had been less accommodating about releasing the Fiesta name, Ford’s first B-segment car might well have been called the Ford Bravo. The Bravo name was reused for a 1981 Fiesta special edition (followed by the 1982 Bravo II) and was subsequently adopted by FIAT. (Author photo)

There had been ongoing rumors in the press about the Bobcat project since at least 1973, but it was not until December 1975 that Ford formally announced the new model, now officially known as the Ford Fiesta.

MK1 FIESTA SPECIFICATIONS

In dimensions and specifications, the Mk1 Fiesta was positioned squarely in the middle of the contemporary B-segment. The Fiesta’s 90-inch (2,286mm) wheelbase was shorter than those of the Renault 5, Peugeot 104, or Volkswagen Polo, but longer than the Fiat 127’s; the Fiesta’s overall length, 140.4 inches (3,565 mm) without bumper guards, made it a bit longer than the Renault or the Polo. (All, of course, were substantially smaller than C-segment cars like the Escort, Chrysler Horizon, or Volkswagen Golf.) There was only one body style, a three-door hatchback, although a van version with no rear quarter windows was added later.

While some rivals used torsion bar springs, the Mk1 Fiesta had coil springs all around. The front suspension was Ford’s customary “track control arm” (TCA) layout of MacPherson struts and lower control arms located by longitudinal compression links. Unlike the early Mk1 Escort, the Fiesta mounted its compression links ahead of the axle line rather than behind it, with no front anti-roll bar, and had a negative scrub radius to promote stability under braking. The rear suspension used a simple beam axle located by trailing links and a Panhard rod. The optional sport suspension added a rear anti-roll bar (though still no front bar) and stiffer springs and shocks.

To minimize costs and reduce unsprung weight, 12-inch wheels were initially standard on all Mk1 Fiestas, although wider wheels and fatter tires were optional. Brakes were front discs and rear drums with an optional vacuum servo.

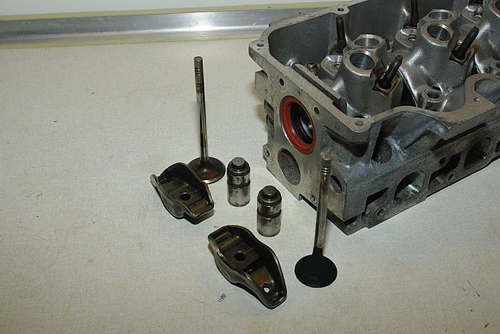

Ford’s pushrod “Valencia” engine (which was not always built in Spain) served the Fiesta line into the nineties. The Valencia, seen here in 1,117 cc (68 cu. in.) form, was based on the long-serving Kent cross-flow engine, but the block was shortened 1.2 inches (30 mm), the bore spacing was reduced, and there were new wedge-shaped combustion chambers instead of the Kent’s Heron head design. (Photo: “Fiesta Mk1 Engine” © 2011 Sam Tait; used with permission)

At launch, all Mk1 Fiestas used a new version of the familiar Kent four. The Fiesta engine was still all-iron, but had a new cylinder head atop a shorter, stiffer, somewhat lighter block with smaller cylinder bores and a new crankshaft with three main bearings rather than five, trading a certain amount of smoothness for reduced internal friction. A longitudinal leading strut limited the engine’s motion on its mounts.

The three-bearing engine was offered in two sizes: 957 cc (58 cu. in.) or 1,117 cc (68 cu. in.). For production convenience, both shared the same 73.96mm (2.91-inch) bore, but the larger engine was stroked from 55.70 mm (2.19 inches) to 64.98 mm (2.56 inches). With a single-throat Ford “sonic idle” carburetor and an 8.3:1 compression ratio, the base “950 LC” engine made 40 PS DIN (29 kW); the high-compression (9.0:1) “950 HC” version added an extra 5 PS (4 kW), but required premium fuel. The bigger “1100” engine, also with 9.0 compression, made 53 PS DIN (39 kW).

The sole transmission was a four-speed manual gearbox driving a separate differential via helical spur gears. Cars with the three-bearing engine had unequal-length halfshafts, the shorter fitted with a harmonic damper; Rzeppa-type CV joints were fitted at each end. Overall gearing was short to make the most of the available power, with final drive ratios of 4.29 for the 950 HC, 4.06 for the 950 LC and 1100.

Early (1976–1979) Mk1 Fiestas were available in base, L, S, and Ghia trim. With bright bumpers and door handles but black window trims, this is probably an L, which had additional sound insulation, a driver’s side mirror (optional on base cars), face-level dashboard vents, reclining seats, and other minor conveniences. Normally, there would also be a chrome strip below the side windows, but this car doesn’t have it. (Photo: “Ford Fiesta first generation” © 2008 Corvette6cr; released into the public domain by the photographer, resized and modified (reduced glare and obscured numberplates) 2013 by Aaron Severson)

While Ford’s recent European models had been produced in both the U.K. and Germany, the Fiesta’s components and even its body panels were sourced from factories throughout Ford’s European empire, in theory allowing Ford to capitalize on the most favorable available labor conditions and also win political points with the governments of various nations. This was not a unique approach (FIAT did the same thing with the 127, whose drivetrains were built in Brazil), but it was new for Ford.

MK1 FIESTA LAUNCH

Mk1 Fiesta pilot production began in May 1976 with the press introduction in June. The new car went on sale in Europe in September, although RHD cars weren’t available until February 1977. The roll-out was marked by one of Ford’s customarily aggressive all-fronts marketing assaults, leaving even the most casual observer with no doubt that Ford had entered the B-segment in force.

Given all the hype, it was no great surprise that the press was somewhat underwhelmed by the product itself. Some reviewers groused that even with all the time and money invested in the Fiesta’s development — the cost, including the Almusafes facility, came out to around $1 billion — Ford had not notably advanced the state of the art. The Mk1 Fiesta was competitive but not class-leading in any single respect, falling somewhat short of the French in ride quality, the Germans in general solidity, and the Italians in joie de vivre.

Press photo of a first-year Mk1 Fiesta Ghia. The Ghia was the top trim level, adding bright exterior trim, velour upholstery, woodgrain dashboard trim, a tachometer, a rear wiper/washer, and, on European cars, halogen headlights. Alloy wheels were initially optional. (Photo: Ford Motor Company)

On the other hand, the Fiesta also had no glaring flaws, something that could not be said of many of its contemporaries. Small cars of the time were often endearing in certain respects and inept or infuriating in others; there was certainly room in the market for a competent generalist that sacrificed outright brilliance for reasonable all-around capability.

This is not to say that the Mk1 Fiesta had no shortcomings. The driving position and outward visibility were good, but base models suffered cheap non-reclining seats and poor interior ventilation, particularly if you didn’t order the optional swing-out vent windows. The trunk had a low liftover height, but mounting the spare tire beneath the floor cut into usable cargo room unless you folded the rear seat flat. Road noise wasn’t bad for the class (particularly on pricier models, which had extra sound insulation), but the three-bearing engines became quite loud when pushed hard. Over time, rust also became a problem.

Even with less than 1,600 lb (725 kg) of curb weight, no early Fiesta was especially quick. With the basic low-compression 957 cc (58 cu. in.) engine, the 0-60 mph (0-97/h) sprint took almost 20 seconds and top speed was only about 80 mph (130 km/h). The 1,117 cc (68 cu. in.) engine boosted top speed to 87-88 mph (140-142 km/h), although independent testers found Ford’s claim of 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) in less than 14 seconds to be optimistic by at least a second. Nonetheless, the Fiesta was fun to drive within its modest limits. With its sport suspension and wider wheels and tires, the Fiesta S was a bit more capable, but the stiffer springs and additional unsprung weight took a noticeable toll on ride quality, which in any case was not as compliant as that of the Renault 5 or Peugeot 104.

Early low-line Mk1 Fiestas had black bumpers (later adopted across the board), door handles, fuel caps, and window surrounds. Spoilers weren’t standard except on the later Super S/Supersport and XR2, but could be ordered from some dealers. (Photo: “FordFiestaPrimeraSerie” © 2006 Randroide; resized 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

Predictably, the Fiesta’s prices put it in the thick of the competition, although the Ford had no commanding price advantage over key rivals. In Germany, a Fiesta 1000 with the low-compression 957 cc engine started at 8,440 DM, 115 DM (about $45) more than a Volkswagen Polo N, while in the U.K., the same Fiesta bowed at £1,856 with tax, £42 (about $75) less than a basic Fiat 127 Special. The 1100S and Ghia were substantially costlier, climbing to £2,657 (almost $4,700) for the latter — £126 (roughly $225) above the quicker, more powerful Renault 5 TS. Interestingly, the Fiesta’s prices overlapped the lower half of the Escort range; a well-equipped Fiesta S or Ghia could easily cost more than a low-line Escort, implying that the Fiesta did indeed cost more to manufacture.

While the Mk1 Fiesta was not a conceptual breakthrough, it was aptly timed and proved an immediate success. It took Ford only 14 months to sell 500,000 copies and just 13 months more to reach 1 million. Demand sometimes exceeded supply, particularly during the energy crisis that followed the 1979 Iranian revolution.

THE FIESTA COMES TO AMERICA

The Mk1 Fiesta also came to America, although, like a reluctant party guest, it arrived late and left early.

Had it not been for the new federal Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) requirements included in the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA — 15 USC 2003) in late 1975, it’s not at all clear that there would have been a U.S. Fiesta at all. While American buyers’ interest in smaller, more fuel-efficient cars perked up considerably in the wake of the 1973 OPEC embargo, even European D-segment sedans like the Cortina were considered dinky by American standards. Ford already had the Pinto and the Maverick for the domestic small car market, and both were doing well.

However, the CAFE standards added a new complication, requiring manufacturers to achieve a minimum fleet-wide average fuel economy — starting at 18 mpg (13.1 L/100 km) for 1978 and 19 mpg (12.4 L/100 km) for 1979 — or pay substantial penalties. In practical terms, that meant that if an automaker was to sell a significant number of big, thirsty cars, they had to be offset by more frugal ones.

Faced with that requirement, federalizing the Fiesta suddenly made more sense. The new law set limits on how many imported cars could be counted toward each automaker’s domestic averages, but each Fiesta sold in the U.S. would still go a long way toward offsetting Ford’s bigger, more profitable LTDs and Thunderbirds.

The benefit would have been even greater if Ford could have built Fiestas in the U.S. or Canada, but considering how much the company had already on the Bobcat project, neither Henry Ford II nor the Finance staff was especially eager to take on the additional expense of retooling Ford’s North American plants. Lee Iacocca and Hal Sperlich also recognized that the European Fiesta was really too small for American tastes.

Sperlich and Iacocca’s proposed solution was to create a bigger spin-off of the Fiesta’s FWD platform for the U.S. market, using powertrains supplied by Honda. Honda was interested, but the plan went over poorly with Henry Ford II, who, according to Iacocca, balked at the idea of a Japanese engine in a Ford car. The deal fell apart and Sperlich was terminated in November 1976.

In hindsight, it appears that Henry’s objections had more to do with his deteriorating relationship with Iacocca than with the merits of the idea. Ford eventually authorized a U.S. version of the front-wheel-drive Mk3 Escort, which, while not exactly the enlarged Fiesta that Iacocca and Sperlich had proposed, nonetheless leveraged the work Ford had done on the Fiesta and shared some of the same components. In 1979, after Iacocca’s departure, Ford acquired an equity stake in the Japanese automaker Toyo Kogyo (Mazda), which would provide transmissions and later share engines and even platforms with some Ford vehicles.

THE FEDERAL FIESTA

In the interim, Ford developed a U.S. version of the Mk1 Fiesta, built at the Saarlouis plant in West Germany with U.S.-sourced glass, electrical systems, and other minor components. U.S.-bound cars also acquired the federally mandated 5 mph (8 km/h) bumpers, which brought the Fiesta’s overall length to 147.1 inches (3,736 mm).

Rather than try to adapt the Fiesta’s European engines for U.S. emissions standards, which probably would have sapped much of the three-bearing engines’ already limited power, Ford opted to install a catalyzed version of the bigger 1,598 cc (98 cu. in.) Kent four. With a compression ratio of 8.5:1, the 1.6-liter engine produced 66 hp SAE (49 kW) and 82 lb-ft (111 N-m) of torque in U.S.-legal form.

In federalized form, the 1,598 cc (98 cu. in.) Kent engine was almost buried beneath its array of emission-control equipment. Despite the mild tune of U.S. engines, the federalized Mk1 Fiesta was quick for a small car of this era. (Photo © 2012 Murilee Martin; used with permission)

Fitting the somewhat larger and heavier five-bearing engine into the Fiesta engine bay entailed some front-end changes, the most notable being the adoption of equal-length halfshafts (via a countershaft from the differential with its own universal joint). The larger engine was accompanied by a taller top gear (0.88 rather than the European cars’ 0.96) and a taller 3.58 axle ratio, allowing more relaxed cruising and pushing the engine’s boomy resonance period well above legal U.S. highway speeds.

Even with taller gearing and more mass — curb weight of the U.S. Fiesta S was listed as 1,835 lb (832 kg), about 185 lb (84 kg) more than a European 1100S — the federalized Fiesta was a good deal quicker than its European counterparts, capable of 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) in less than 11 seconds and a top speed of around 100 mph (160 km/h). The bigger engine brought little penalty in fuel economy, although engine noise was still high.

The U.S. Fiesta went on sale in August 1977, arriving to generally positive reviews and healthy buyer interest. However, importing federalized cars from Germany imposed some practical limits on U.S. sales. One was plant capacity; with such strong demand for the Fiesta in Europe, Ford decided to cap Saarlouis production of the federalized car so that it would not cut into European sales. Another issue was that German production left the Fiesta vulnerable to fluctuations in the relative values of the dollar and the Deutschmark, making it hard to keep prices low. At launch, a U.S.-market base Fiesta listed for only $3,680, but base price spiked by almost 15% for 1979, pitting the Fiesta against some bigger, roomier C-segment cars like the FWD Plymouth Horizon and the RWD Chevrolet Chevette.

A third issue, and the one that ultimately set the pace for U.S. Fiesta sales, was the CAFE limits. Ford had allotted enough plant capacity to build up to 100,000 federalized cars per year, but under the formula established by EPCA, anything beyond the company’s “includable base import volume” — which for Ford was 75,200 units for MY1978 and probably a comparable number for MY1979 — would be treated as a separate import fleet for CAFE purposes. For the 1980 model year and beyond, Ford’s domestic fuel economy average could only include cars with at least 75% U.S. and/or Canadian content.

A battered junkyard example of the U.S.-spec Mk1 Fiesta shows off the hefty 5 mph (8 km/h) bumpers added to meet federal safety standards. Except for the larger engine, the U.S. Fiesta S was similar to the European version, adding sport seats, a tachometer, 155SR-12 tires, a sport suspension with rear anti-roll bar, and the distinctive S stripes. (Photo © 2012 Murilee Martin; used with permission)

Ford could have alleviated most of these issues by setting up a North American production line for the Fiesta, but with development of the U.S.-market Escort already well underway, that wasn’t going to happen. The imported Fiesta remained in the Ford lineup through the 1980 model year, bridging the gap until the Escort was ready, but disappeared before January 1981. Production of the U.S.-spec Mk1 Fiesta totaled 263,398 units.

The Fiesta wouldn’t return to the States for more than 25 years, although for a time, the cheaper Korean-built, Mazda-based Ford Festiva occupied a similar place in Ford’s U.S. lineup.

FIESTA 1300S AND HEALEY FIESTA

Shortly after the U.S. Fiesta went on sale, Ford also added the first European Mk1 Fiesta model with the five-bearing Kent engine: the Fiesta 1300S and 1300 Ghia, powered by the 1,298 cc (79 cu. in.) engine also found in the Capri, Cortina, and Escort 1300. With 9.2:1 compression and a two-throat Weber 32/32 DFT carburetor, the Fiesta 1300 was nearly as powerful as the bigger U.S. engine, with 66 PS DIN (49 kW), but couldn’t match the larger engine’s torque. The 1300 also included a taller (3.84) axle ratio.

The extra power was appreciated, but the Fiesta 1300S was still not a hot hatch. It was capable of an advertised and realistic 98 mph (158 km/h), but independent testers once again failed to equal Ford’s claimed 10.7-second 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) time, which meant the Fiesta was still no match for the 1,397 cc (85 cu. in.) Renault 5 Alpine/Gordini. The 1300S also wasn’t substantially quicker than a well-tuned 1100S like the contemporary Jansport 1100 or the limited-production Fiesta Special offered in the German market in 1979, which extracted 70 PS DIN (52 kW) from the 1,117 cc (68 cu. in.) engine.

Surprisingly, Ford did not rush to install the bigger 1,598 cc (98 cu. in.) engine in the European Fiesta, although that move would have given performance a shot in the arm and been a boon to racers campaigning the Fiesta in Group 1 competition. Since the advent of the U.S. Fiesta, teams had been able to use the bigger engine, but Group 1 rules limited them to the restrictive federalized cylinder head, a serious performance handicap. In 1979, the Ford works rally team ran two more extensively modified 1.6-liter Group 2 Fiestas making close to 100 hp/liter, but the cars were underdeveloped and the results disappointing.

In 1978, at the suggestion of a Detroit-area businessman named Gary Kohs, Ford commissioned England’s Donald Healey to develop a sporty Healey Fiesta concept car. This was based on the U.S. Fiesta, but used the freer-breathing cylinder head from the Escort 1600 Sport (and the old Escort Mexico and Cortina GT) and had various performance modifications, including 10.0:1 compression, a hotter camshaft, a Weber 32/36 DGV carburetor, and a low-restriction exhaust system. The engine’s estimated 105 hp SAE (78 kW) was matched with an upgraded chassis, fatter tires on 6Jx13 Minilite wheels, and a roll cage.

The one and only Healey Fiesta marked the end of one dynasty (it was the final Healey-badged car) and the beginning of a new one, foreshadowing the long line of sporty Fiestas that followed. The Healey prototype was a bit racier than the later XR2, featuring a ported head, tubular exhaust headers, Wolfrace sport seats, Motolito sport steering wheel, Minilite alloy wheels, a roll cage, and the shorter 4.29 axle ratio of the European Fiesta 950 HC. Despite the removal of the rear seat and emissions equipment, the Healey Fiesta weighed about 45 lb (20 kg) more than a stock U.S.-spec Fiesta S. (Photo: “Healey Fiesta” © 2006 Bob Segui; used with permission)

Only a single Healey Fiesta prototype was built, painted British Racing Green with gold wheels and pinstripes. Ford exhibited it at various auto shows in 1979 and allowed U.S. automotive writers to drive it, but it was never intended for production. Even if it had been, it probably wouldn’t have been offered in the States (since Ford had already decided to drop the U.S. Fiesta once the FWD Escort was ready) and in any case wouldn’t have been street legal there in the form exhibited; the prototype had no emissions equipment.

FIESTA X-PACK AND SUPERSPORT

While the Healey Fiesta wasn’t for public consumption (although the prototype still exists in private hands), British and European buyers could order some similar pieces through Ford’s network of Rallye Sport dealers.

To make up for the demise of Ford’s Advanced Vehicle Operations (FAVO) and its specialized RS homologation models a few years earlier, Ford developed a series of “Series X” packs for its most popular models, including the Fiesta. Some of that equipment was cosmetic (polyurethane spoilers and fender flares, RS alloy wheels), but there were also performance items like bigger front disc brakes, Bilstein shocks, and freer-breathing exhaust systems.

By late 1979, you could also order a Fiesta X with the 1,598 cc (98 cu. in.) five-bearing engine, the Escort Sport head, and a two-throat Weber 34 DATR carburetor, good for a claimed 90 PS (66 kW) and 94 lb-ft (127 N-m) of torque. Unfortunately, this was not a production option, but a rather expensive dealer swap, costing almost £800 (around $1,800) plus labor on an exchange basis. Adding the engine and every non-conflicting item in the catalog brought the X-pack tally to around £2,200 (almost $5,000) with labor, which of course did not include the cost of the car itself. We don’t know how many X-pack Fiestas were sold; we assume that most buyers settled for selected pieces rather than the full kit.

The logical next step would have seemed to be a production Fiesta 1600 for the European market, but for the 1981 model year, Ford instead offered the mostly cosmetic Fiesta Supersport/Super S, which combined stock mechanicals with a body kit, spoilers, and 13-inch RS wheels. (British Supersports were all based on the 1300S, but the similar Super S model offered in some other markets could also be ordered with the 1,117 cc (68 cu. in.) engine.)

A 1982 Ford Fiesta Supersport shows off its fender flares, bumper overriders and driving lamps (optional on lesser Fiestas), tape stripes, and polished 13×6 RS alloys. The Supersport looks much like the Mk1 XR2, some examples of which now sport the same wheels. The obvious tip-off is that Supersports have rectangular rather than round headlights. The blue car in the background is a contemporary Mk1 Fiesta van. (Photo: “MARCH 1982 FORD FIESTA MK1 1298cc SUPERSPORT WBW922X” © 2009 John Catlow – U.K.; used with permission)

Some sources describe the Supersport as a marketing trial balloon, although after the 1300S, the Healey Fiesta, and the X-packs, one has to wonder how many times Ford needed to test the waters before jumping in. Given its timing, the Supersport strikes us more as a holding action. There may indeed have been some temporary doubts about the market — the 1979 fuel crisis had shifted buyers’ attention back toward smaller-engined models and prompted Ford to introduce a more-frugal Economy version of the Fiesta 1100 — but development of a sporty 1.6-liter Fiesta was already under way.

FIESTA XR2 MK1

At the 1981 IAA show in Frankfurt, Ford finally introduced its first real Fiesta hot hatch: the Fiesta XR2. It was developed by the new Special Vehicle Engineering (SVE) unit, established in February 1980 as the modern successor to the old FAVO operation, albeit without the separate production line that had ultimately made FAVO too expensive to continue. The XR2 was SVE’s second car, debuting about six months after their first project, the Capri 2.8 Injection. The latter was presumably the reason the Fiesta XR2 didn’t appear sooner than it did; SVE’s personnel and resources were limited.

After all the lead-up, the XR2’s specifications were almost anticlimactic. The engine was the five-bearing 1,598 cc (98 cu. in.) Kent unit fitted with the Mexico head and cam and the Weber 32/34 DFTA carburetor from the Escort XR3 (subsequently replaced with a Weber DFT6), which yielded the same 84 PS (62 kW) and 92 lb-ft (125 N-m) of torque as the old rear-drive Escort 1600 Sport. The engine was lowered 0.6 inches (15 mm) in the chassis and mated to the FWD Escort’s sturdier four-speed transmission and the taller 3.58 axle ratio from the now-defunct U.S. Fiesta.

The XR2 was the only European Mk1 Fiesta with round headlights. (Normally, there were also driving lamps on the front bumper as well, but they’re missing on this car.) The paint job was also unique, as were the sport seats, two-spoke steering wheel, and “Shark Grey” upholstery, although the interior fitments were otherwise a combination of Ghia and S pieces. (Photo: “Ford Fiesta XR2 Sitting In A Supermarket Car Park In The West End Of Glasgow Scotland – 4 Of 5” © 2012 Kelvin; used with permission)

The XR2’s suspension was basically that of the 1300S, but with shortened front springs to lower the nose about an inch (25 mm). An X-pack body kit and fender flares allowed wider 13×6 alloy wheels (modeled on but not identical to Wolfrace Sonic wheels), which in turn accommodated bigger vented front discs and a set of 185/60HR-13 Pirelli P6s. In all, the XR2 differed only in detail from the previous X-pack cars. The only really surprising thing about it was that Ford had waited so long to create what was basically a straightforward amalgamation of familiar pieces.

The price for all this was 15,700 DM in Germany, £5,500 in the U.K. (reduced to £5,150 in mid-1982), which was cheaper than an X-pack Fiesta with all the trimmings, but not exactly a bargain; the Fiesta XR2 was substantially more expensive than rivals like the Fiat 127 1300GT, Alfa Romeo Alfasud 1.5, or the more powerful Renault 5 Alpine/Gordini. (Interestingly, at least in the U.K., the XR2 was priced identically to the 1300 Ghia, which was slower and softer, but somewhat better-equipped.)

In a straight line, the XR2 was capable of 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) in the mid-9s with a top speed of perhaps 105 mph (169 km/h), which was not in the same league as the bigger but more expensive Volkswagen Golf GTi or Escort XR3i, but a good deal quicker than most cars in the XR2’s size and price class. Unfortunately, the XR2 was also thirstier than lesser Fiestas and many rivals, returning only 24-25 mpg (9.4-9.8 L/100 km) on premium fuel.

The XR2 had agile handling and excellent grip from its fat Pirellis, but civility was not a strong point. Noise levels were high and the firmer suspension and bigger wheels made the ride decidedly choppy. The wide tires were also prone to tramlining over uneven surfaces, which did the Fiesta’s high-speed stability no particular favors.

The Mk1 Fiesta XR2’s fender flares (basically the same as the ones used by the X-pack and Supersport cars) were ABS plastic while the front and rear spoilers were polyurethane — and relatively soft to comply with German laws on pedestrian safety. All the extra equipment made the XR2 about 90 lb (41 kg) heavier than a Fiesta 1300 S. (Photo: “Ford Fiesta XR2 Sitting In A Supermarket Car Park In The West End Of Glasgow Scotland – 1 Of 5” © 2012 Kelvin; used with permission)

The usual critics had mixed feelings about the Mk1 XR2, adjudging it fun to drive, but neither especially comfortable in calmer use nor an outstanding value for the money. The intended audience had no such reservations. The Fiesta XR2 was the latest in a long and generally illustrious line of fast Fords, and if it was not the fastest or most polished car in its class, it felt racy (albeit sometimes more than its objective performance could really justify). Younger buyers responded enthusiastically, with a predictable effect on insurance rates, and the XR2 became a profitable image leader.

MK2 FIESTA

When the XR2 debuted, the Mk1 Fiesta was already five years old. It had received surprisingly few changes during that time: new trim levels (cheaper Popular and Popular Plus and the mid-level GL) for 1980; new black bumpers for all models in 1981 and an optional 1100 Economy package that sought to improve fuel consumption with taller gearing, a variable-venturi carburetor, and vacuum-triggered economy and upshift lights; and for 1982, 13-inch wheels for the Fiesta S and softer suspensions for most models except the XR2. There was also a lengthy series of special editions with unique trim and extra equipment.

This Mk1 Fiesta is a 1983 Ghia; look closely and you can see the telltale badge on the front fender ahead of the door. Late Mk1 Ghias had satin-finish black rather than bright bumpers, but retained chrome windshield and window surrounds. The 1983 edition now had standard alloy wheels, tinted windows, and a tilt-up sunroof. (Photo: “1983 Ford Fiesta Mk. I 1.3 Ghia” © 2013 Zack Stiling; used with permission)

While the Mk1 Fiesta was still selling briskly (total production had passed the 2 million unit mark in 1981), it was competing in an increasingly crowded segment. Compared to newer rivals like the Fiat Uno, Peugeot 205, and Austin/MG Metro (which displaced the Fiesta from its position as Britain’s best-selling car), the Fiesta was starting to look its age.

In the fall of 1983, Ford unveiled the Mk2 Fiesta. The Mk2 occupied the hazy middle ground between facelift and all-new car, featuring a slightly wider, somewhat longer body (on an unchanged wheelbase) and freshened styling. The revised body tidied up the Fiesta’s dated aerodynamics — although the new car’s 0.40 Cd was still unimpressive for the mid-eighties — and provided space in the engine bay for Ford’s new SOHC CVH engine, which was gradually replacing the five-bearing pushrod Kent. Also added with the revamp were a faster steering ratio, standard 13-inch wheels, and an optional five-speed gearbox borrowed from the FWD Escort.

The restyled Mk2 Fiesta still rode a 90.1-inch (2,289mm) wheelbase, but was now 143.6 inches (3,647 mm) overall; XR2 and Ghia cars stretched an additional 2.5 inches (64 mm) due to their standard bumper overriders. (Photo: “1988 Ford Fiesta Popular”, a modified version (created 2013 by Mr.choppers) of the photo “1988 Ford Fiesta Popular” © 2009 Rob; resized 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license)

The three-bearing “Valencia” pushrod fours continued for low-line Mk2 Fiestas, although the 957 cc (58 cu. in.) versions were consolidated into one and the 1,117 cc (68 cu. in.) engine was retuned for greater torque at some cost in power. Both engines now had Ford’s variable-venturi carburetor, which was supposed to provide better fuel economy. Shortly after launch, there was also a 1,608 cc (98 cu. in.) diesel with 54 PS (40 kW). A new Fiesta 1300 with a 1,296 cc (79 cu. in.) CVH engine and 69 PS DIN (51 kW) followed in the spring of 1984, although this was to be short-lived. It was replaced in 1986 by a 74 PS (54 kW) 1,392 cc (85 cu. in.) “lean burn” engine with a narrower bore, a longer stroke, and the ability to run at air-fuel mixtures of around 18:1 in the interests of lower emissions. Later, there was also a 1,297 cc (79 cu. in.) five-bearing version of the pushrod Valencia engine, created to resolve certain engine production capacity issues.

With the Mk2, Ford attempted to improve the Fiesta’s ride, which had come in for a fair amount of criticism. The results were not wholly successful: The Mk2 Fiesta’s ride was still busy, although better sound insulation made it quieter than before. Some testers also complained that the combination of greater body lean and lighter, quicker steering made the Fiesta feel more nervous in sudden maneuvers than its actual dynamics merited. It was nonetheless one of the better-handling cars in its class, if not on the same level as the Peugeot 205.

Added to the Mk2 Fiesta line in 1984, Ford’s CVH (Compound Valve angle, Hemispherical chamber) engine was a SOHC eight-valve design intended to provide the breathing advantages of hemispherical combustion chambers with only a single overhead camshaft. The splayed valves are actuated by rocker arms pivoting on hydraulic lash adjusters, obviating the need for routine valve adjustments. (Photo: “CVH Kopf2” © 2012 Luitold; resized 2013 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

In all, the Mk2 Fiesta remained a mid-pack performer whose greatest single virtue was Ford’s attention to minor details. The Fiesta, particularly in Ghia trim, was what an average buyer might term “a nice little car,” with a reasonably quiet cabin, pleasant trim, and good ergonomics. The smaller Metro was better packaged, a Honda Civic was faster, and the Peugeot 205 had the better chassis, but the Fiesta was a respectable compromise.

FORD FIESTA XR2 MK2

The Mk2 Fiesta XR2 debuted in May 1984. Again the work of SVE, the new XR2 was much like its predecessor, but traded the 1,598 cc (98 cu. in.) Kent for the newer 1,596 cc (97 cu. in.) CVH engine. This engine, previously seen in the recently superseded Escort XR3, had a single Weber carburetor rather than the Bosch K-Jetronic injection of the latest Escort XR3i, but still boasted 96 PS DIN (71 kW) and 98 lb-ft (133 N-m) of torque, useful improvements over the previous XR2. A five-speed gearbox and gas shocks were standard equipment.

While the Mk1 Fiesta XR2 had standard alloy wheels, alloys were optional on the Mk2, presumably in an effort to keep the list price down; this car still wears the standard steel wheels and unusual XR2 wheelcovers. Driving lamps, bumper overriders, a front spoiler, and dual outside mirrors were standard on the Mk2 Fiesta XR2, as were the fender flares and black rocker extensions. (Photo: “Ford Fiesta XR2” 2013 David Austin; used with permission)

With additional power and little-changed curb weight, the new XR2 promised sprightly performance: Ford claimed 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) in 8.7 seconds a top speed of 112 mph (180 km/h). Independent testers again found those figures hard to replicate, concluding that the new XR2 was not substantially quicker than its predecessor. While the CVH engine’s overhead camshaft and hemispherical combustion chambers theoretically made it a freer-breathing, higher-revving engine than the pushrod Kent, the OHC four’s muscle was concentrated at significantly higher engine speeds, which meant it had to be pushed harder to extract the same performance. Worse, the CVH engine was none too pleasant when you really applied the spurs; the word “thrashy” appears frequently in contemporary reviews.

This 1988 Mk2 Fiesta XR2 looks appropriately menacing in black, which was a relatively uncommon choice on Mk1 and Mk2 Fiestas (and generally an extra-cost option, to boot). Note the red bumper highlights, another standard XR2 cosmetic touch, and the turn signal repeaters just ahead of the doors, added in 1986. (Photo: “Ford Fiesta Mk2 XR2” © 2013 Paul Bennett; used with permission)

In other respects, the XR2’s personality hadn’t changed. The ride was incrementally softer, though still far from supple, but the crisp turn-in and cornering grip that had made the first car a favorite of boy racers were undiminished. Automotive reviewers tended to prefer the Peugeot 205GTi, which had a sweeter engine and an even sharper chassis, but the Peugeot’s more neutral balance could be a double-edged sword; the Ford was less likely to bite back, at least as long as the road was relatively smooth. The XR2’s aggressive persona (combined with Ford’s considerable marketing muscle) kept the Fiesta a consistently strong player in this class, if not the frontrunner.

The Mk2 Fiesta XR2 sported an under-bumper rear valance with fog lights and a black surround on the tailgate, replacing the previous rear spoiler. (Photo: “Ford Fiesta Mk2 XR2” © 2013 Paul Bennett; used with permission)

THE PARTY CONTINUES

The Mk2 Fiesta remained on sale into 1989, when it was replaced by the all-new third-generation car. Total production for the Mk1 and Mk2 Fiesta was more than 4.9 million units, which represents a very respectable average of more than 400,000 units a year, with peaks approaching half a million. That’s about what Ford anticipated during the Fiesta’s development, so it appears that despite the initial fears, the company eventually got its money’s worth.

The Mk3 Fiesta was notably bigger than before, now stretching 147.4 inches (3,744 mm) long on an extended 96.3-inch (2,446mm) wheelbase, while overall width (with dual mirrors) was up to 73 inches (1,854 mm). As seen in this 1989 press shot, the Mk3 Fiesta was now available in five-door form as well as the familiar three-door. Bigger dimensions and more glass area increased curb weight around 110 lb (50 kg), depending on model. (Photo: Ford Motor Company)

The Fiesta is now one of Ford’s longest-lived nameplates. Many of its original rivals are long gone, and while today newer models fill most of the same roles, the fact that Ford has kept the Fiesta name for almost four decades says a great deal about its success in this class. Its critical standing has fluctuated over the years and it’s no longer no small as it once was (the recent U.S.-market four-door sedan is about the size of a Mk2 Cortina), but the Fiesta remains one of the benchmarks of the B-segment.

That might not be a sexy achievement or the sort that gets much recognition from automotive historians, but it is nonetheless a considerable one. Entering a new market segment, especially one that requires a heavy investment in new technology, isn’t easy under the best of circumstances. Over the years, many companies have fallen on their faces in the attempt, and when the company makes the move reluctantly, the potential for disaster is great.

The Mk3 Fiesta XR2i initially retained the 1,596 cc (97 cu. in.) CVH engine, albeit now with Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection and Ford’s EEC-IV engine management system, but in mid-1992, the CVH was replaced by the 1,796 cc (110 cu. in.) DOHC 16-valve Zeta engine, which gave up 5 hp (3.7 kW) in exchange for about 10% more torque. An interesting option on the XR2i and other Mk3 Fiestas was the Lucas-Girling Stop Control System, a two-channel mechanical antilock braking system. (Photo: Ford Motor Company)

Viewed in that light, the Mk1 Fiesta’s simple competence can be seen as the victory it was. In many respects, creating a decent, cheap small car is a bigger challenge than building a winning race car. A racer can be ruthlessly optimized for a single purpose; a mass-market supermini has to perform at least passably well in a multitude of ways for a broad range of buyers. Moreover, in this class, excellence in one area usually brings a corresponding penalty in others. More cargo room means less passenger space; better performance cuts into fuel economy; and the technological solutions that allow bigger, more expensive cars to have their cake and eat it too tend to push the price too high for many B-segment buyers to afford.

All that was even more true in the Mk1 Fiesta’s heyday than it is today, a fact that Ford clearly recognized. The original Fiesta was not an extraordinary car, but that was not its purpose. Its goal was to be good enough, and in that sense, the Fiesta came as close as any car of its time to making a virtue of compromise.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In July 2023, almost 10 years after the original publication of this article, production of the Ford Fiesta finally ceased after 47 years and more than 20 million cars sold worldwide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank David Austin, Paul Bennett, John Catlow, Kelvin, Murilee Martin, Bob Segui, Jack Stiling, Sam Tait, and Ford Motor Company Archives for allowing us to use their images in this article.

NOTES ON SOURCES

Our sources on the development and performance of the Fiesta included “AutoTest: Ford Capri 2.8i: Straightforward enjoyment,” Autocar 20 June 1981, reprinted in High Performance Capris Gold Portfolio 1969-1987, ed. R.M. Clarke (Cobham, England: Brooklands Books Ltd., ca. 1990): 88–93; “AutoTest: Ford Fiesta 1000L,” Autocar 27 October 1976: 68–74; “AutoTest: Ford Fiesta 1.1 Ghia: A touch of class,” Autocar 22 October 1983: 46–51; “AutoTest: Ford Fiesta XR2,” Autocar 19 December 1981, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991, ed. R.M. Clarke (Cobham, England: Brooklands Books Ltd., ca. 1992): 22–27; “AutoTest: Ford Fiesta XR2,” Autocar 16 June 1984, reprinted in ibid: 32–37; E. Azplilicueta and A. Andres, “La Familia Ford,” Autopista 6 March 1976: 8–14; “Bag a Bargain!” Classic Ford June 2006: 78–81; “Basic buys (Group test: Bargain Hatchbacks),” What Car? January 1985: 26–34; Patrick Bedard, “Celebrating the Ford Fiesta,” Car and Driver Vol. 22, No. 7 (January 1977): 58–61, 89; “Bericht: 35 Jahre Ford Fiesta: Stilvolle Einkaufstasche,” Auto Scout 24, 3 March 2011, ww2.autoscout24. de, accessed 18 May 2013; “Big Hearted Baby,” Fast Lane November 1987, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 48–51; Kevin Blick, “Grudge Match: Ford Fiesta RS Turbo v. Peugeot 205 GTI 1.9,” Performance Car August 1990, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 88–95; William Boddy, “Fast Fiesta: The New Ford XR-2,” Motor Sport January 1982: 28, “Ford Fiesta 1.1 ‘S,'” Motor Sport July 1979: 978, “Fun with a Fiesta XR-2,” Motor Sport February 1982: 315, and “The Ford Fiesta 1.3 Ghia — An Appreciation, Motor Sport May 1980: 637; John Bolster, “Fiesta: Ford stir the pudding,” Autosport 17 March 1977: 48, and “Ford’s mini challenge,” Autosport 15 July 1976: 41; J. Bonilla, “Historia Bobcat,” Motor Clásico June 2009: 20–23, and “Imagen deportiva: Super Sport y XR2,” Motor Clásico June 2009: 24–31; Gérard Bordenave, “Ford of Europe, 1967-2003,” Cahiers du GRES [Groupement de Recherches Economiques et Sociales, Université Monteqsquie-Bordeaux and Université des Sciences Sociales Tolouse], Cahier No. 2003-11 (September 2003); “Brief Test: Ford Fiesta 1.1 L Economy,” Motor 31 July 1982: 30–31; Richard Bremner, “Ford Fiesta 1.25,” Autocar 2 December 2005; “Brief Test: Ford Fiesta 1300S,” Motor 8 October 1977; Russell Brookes, “Fireball Fiesta,” Motor 12 May 1979 [nn]; “Butch Baby,” Motor 29 November 1980, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 16–18; Rich Ceppos, “4000-mile test of the new Ford Fiesta,” Popular Science Vol. 211, No. 1 (July 1977): 76–77, 134; “Changing Guard (Giant Test: Fiat Uno Selecta -v- Ford Fiesta 1.1 Auto -v- Metro 1.3 Auto), CAR September 1987: 134–141; “City Slickers,” What Car? October 1987: 46–69; “City slickers (Group test: luxury superminis),” What Car? February 1985: 24–28; “Compartif: 13 Sportives de Moins de 45 000 F, Echappement November 1979: 42–63; Dirk-Michael Conradt and Gëtz Leyrer, “Die Kleinen mit der großsen Klappe. Der VW Golf und seine Konkurrenten,” Auto Motor und Sport 10/1979 (9 May 1979): 80-94; Mike Covello, Standard Catalog of Imported Cars 1946-2002, Second Edition (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2001); Jesse Crosse, “Moving Up,” Performance Car April 1989, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 54–58; “Dauertest: Ford Fiesta 1.1 S: Reifezeugnis: 50.000 km-Dauertest: Wie ausgereift ist der Ford Fiesta?” Auto Motor und Sport 21/1977 (12 October 1977): 36–47; “Documento Exclusivo: Bob-Cat: El Ford Español de la Pequeña Cilindrada,” Autopista 5 January 1974: 19–20; “Duds and Duffers,” CAR November 1986: 178–180; Jim Dunne, “Detroit Report,” Popular Science Vol. 203, No. 4 (October 1973): 40; “Economy Superstars (Group Test: Diesel Superminis),” What Car? September 1985: 34–40; Helmut Eicker, “Teure Technik. Wie Ford den Fiesta baute,” Auto Motor und Sport 21/1976 (13 Oct. 1976): 84-94; “Europe’s Most Successful New Car in History Comes to America” [advertisement], Popular Mechanics Vol. 148, No. 5 (November 1977): 51–53; “Fiesta Special,” Classic Ford June 2006: 66–68; “Fiesta XR2i -v- 205 GTI,” Autocar & Motor 25 October 1989, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 64–69; “Ford Fiesta,” A to Z of Classic Cars, Classic & Sports Car, 5 May 2011, www.classicandsportscar. com, accessed 12 June 2013; “Ford Fiesta Ghia,” Road & Track Vol. 28, No. 11 (July 1977): 58–61; the Ford Fiesta Mk 1 website, www.fiesta-mk1. co.uk, last accessed 6 November 2013; “Ford Fiesta 1.4S,” Motor 2 August 1986, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 44–47; “Ford Fiesta S,” Car and Driver Vol. 23, No. 1 (July 1977): 91–100; “Ford Fiesta to use dry DCT, while Focus will have planetary auto,” DrivelineNEWS, 9 January 2013, drivelinenews. com, accessed 4 November 2013; “Ford Fight Back (Group Test: Supermini Hatchbacks),” What Car? June 1984: 60–71; Ford Motor Company, “Production of New PowerShift Dual-Clutch Automatic for New 2011 Ford Fiesta” [press release], 29 March 2010; Ford Motor Company Ltd., Cars [brochure FA221/125], September 1987; Cars December ’84 / January ’85 [brochure FA221/103], December 1984; CARS May 1983 [brochure FA221/88], May 1983; “Fiesta 3-door Model Showcases the New Durashift EST Transmission” [press release], 18 June 2003; Ford Cars (All Model Catalogue) July/August 1979 [brochure FA101], June 1979; Ford Cars (All Model Catalogue) [brochure FA221/58], June 1980; Ford Cars (All Model Catalogue) [brochure FA101], January 1981; Ford Cars (All Model Catalogue) [brochure FA 211/68], June 1981; Ford Cars (All Model Catalogue October-November 1982) [brochure FA221/83], September 1982; “The New Ford Fiesta, Oh what a beautiful baby!” [brochure FA 254], c. February 1977; “The new Ford Fiesta: Oh what a beautiful baby!” [advertisement] CAR March 1977: 1–2; “The new Fiesta 1300. Now the little car thinks even bigger,” advertisement, 1984; Ford-Werke AG, “Ford Fiesta,” brochure No. 60115, August 1976; “Ford’s happy event,” Autocar 17 July 1976: 12–21; “Fun in a Fiesta,” What Car? August 1990, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 87; Jack Galusha, “Ford Fiesta 1.6,” Autocar 21 March 2005; “Geared for success,” What Car May 1979: 17–24; “Giant Test: Fiat 127 Sport -v- Ford Fiesta 1.1S -v- Peugeot 104 ZS,” CAR March 1979: 58–67; “Giant Test: Ford Fiesta XR2 -v- MG Metro Turbo -v- Peugeot 205 GTi,” CAR December 1984: 136–145; “Giant Test: MG Metro -v- Ford Fiesta XR2 -v- Fiat 127GT,” CAR October 1982: 80–86; “Giant Test: Fiat Panda -v- Ford Fiesta 1.0 -v- Austin Metro 1.0,” CAR October 1981: 64-71; “Giant Test Special: Finding Out,” CAR April 1989: 104–118; “Giant Test Special: Renault 5TX -v- MG Metro -v- Ford Fiesta XR2 -v- Citroën Vista GT -v- Fiat 127GT,” CAR June 1983: 108–116; “Giant Test: The Joker Wins: Skoda Favorit 136 LX -v- Ford Fiesta 1.0 Popular,” CAR December 1989: 128–135; “Giant Test: Town & Country Club,” CAR August 1994: 104–121; “Giant Test: VW Polo -v- Peugeot 104 -v- Ford Fiesta -v- Renault 5 -v- Fiat 127 -v- Mini 1000,” CAR March 1977: 42–49; “Great X-packtations,” Motor 17 November 1979, reprinted in High Performance Capris Gold Portfolio 1969-1987: 80–81; “Group Test: Triple Blast,” Motor 7 July 1984: 10–15; David Halberstam, The Reckoning (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1986); Chris Harvey, “The Cars: Keith Ripp,” Auto Performance March 1983: 41–45; Fred Henderson, “Looking Back?” Cars and Car Conversions October 1980: 74–75; Kim Henson, “Buyer’s Guide: MkI Fiesta,” Classic Ford February 2005: 92–98; Tony Hogg, “Healey Fiesta: Donald Healey works his magic,” Road & Track Vol. 30, No. 12 (August 1979): 38–40; Friedbert Holz, “Grosse Klasse, Kleine Masse (Vergleichstest: Ford Fiesta 1300S – Renault 5 TS),” Sport Auto January 1980: 82–86; Dave Holls and Michael Lamm, A Century of Automotive Style: 100 Years of American Car Design (Stockton, CA: Lamm-Morada Publishing Co. Inc., 1997); Paul Horrell, “Newcomers: Ford Fiesta,” CAR November 1995: 196, 199; Mark Hughes, “Fiesta Frolics” and “Is there a quicker Fiesta?” Autosport 20 May 1982, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 28–29; Ray Hutton, “Ford Fiesta: Ford’s small success gets bigger,” Car and Driver Vol. 34, No. 11 (May 1989): 38; Lee Iacocca with William Novak, Iacocca: An Autobiography (New York: Bantam Books, 1984); L.A. Izquierdo, “Marketing y competición: Fiesta 1600 Gr.2,” Motor Clásico June 2009: 34–39; Erik Johnson, “2014 Ford Fiesta 1.0L EcoBoost,” Car and Driver November 2012, www.caranddriver. com, accessed 4 November 2013; and “2014 Ford Fiesta Sedan and Hatchback,” ibid, www.caranddriver. com, accessed 4 November 2013; Graham Jones, “The Specials,” Cars and Car Conversions June 1982: 30–34; Jeff Koch, “Healey Fiesta,” Hemmings Sports & Exotic Car #13 (September 2006); Tony Kyd, “12,000 Miles On: Taut Fiesta,” Motor 4 February 1978: 34–36; Michael Lamm, “Driving the Ford Fiesta,” Popular Mechanics Vol. 148, No. 1 (July 1977): 54–56; Damon Lavrinc, “Tokyo 2007 Preview: Honda showing CR-Z Concept,” Autoblog, 9 October 2007, www.autoblog. com, accessed 25 December 2013; Barry Lee, “Laying It on the Line,” Cars and Car Conversions April 1978: 46–48, and “Laying It on the Line,” Cars and Car Conversions May 1978: 47–49; Götz Leyrer, “Der große Preis: Fiesta Super,” Auto Motor und Sport 11/1979 (23 May 1979): 38-45; Annamaria Lösch, ed., World Cars 1979 (Rome: L’Editrice dell’Automobile LEA/New York: Herald Books, 1979), and World Cars 1985 (New York: Herald Books, 1985); Robert Lund, “Detroit Listening Post,” Popular Mechanics Vol. 149, No. 2 (February 1978): 44; MAC, “Smooth New Ford Automatics for Fiesta and Fusion,” Carpages, 30 January 2004, www.carpages. co.uk, accessed 4 November 2013; James May, “Long Term: Ford Fiesta RS Turbo,” Autocar & Motor 17 April 1991, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 96–99; Neil McIntee, “Hot Metal,” Autocar 3 August 1988: 42–49; Russell Martin, “Seal of Approval,” Classic Ford July 2006: 84–87; Mike McCarthy, “Fast and Furious,” Autosport 31 January 1985, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 42–43; Alex Meredith, “SIA Interview: Donald Healey,” Special Interest Autos No. 67 (February 1982): 58–62; “Metro v. Fiesta: Wheel to Wheel comparison,” Autocar 28 February 1981: 20–24; “Neuheiten: Fiesta Super S/Escort 1980,” Auto Zeitung 23 July 1980: 20; “New Fiesta GL – the finishing touch” [advertisement] CAR March 1980: 10; Paul Niedermeyer, “Curbside Classic: 1978 Ford Fiesta — Here Today, Gone Tomorrow,” Curbside Classic, 26 February 2013, www.curbsideclassic. com/ curbside-classics-american/ curbside-classic-1978-ford-fiesta- here-today-gone-tomorrow/, accessed 18 May 2013; Jan P. Norbye, “The new logic in small-car engineering,” Popular Science Vol. 206, No. 2 (February 1975): 56–59, and “The View Down the Road,” Popular Science Vol. 205, No. 6 (December 1974): 37; Jan P. Norbye and Jim Dunne, “Economy imports: for people serious about saving fuel,” Popular Science Vol. 205, No. 1 (July 1974): 30–43; Jason O’Halloran, “Q Jumping,” Classic Ford October 2003: 8–13; “Oh, you beautiful baby! New ‘Series X’ small wheel arch kit for your Fiesta” [Advertisement] CAR March 1979: 12; “Olé XR2: New sporting model for Fiesta,” Autocar 5 September 1981, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 19; “Overtaking Notes No. 14: Ford Fiesta,” CAR November 1995: 13; Ed Pearson, “Goin’ racing: Fiesta Race Championship 1981,” Popular Motoring May 1981 [nn]; Jon Quirk, “Ford Fiesta 1.4 TDCi,” Autocar 20 January 2006; “Road Test: Ford Fiesta 1.1L Five-Speed,” Motor 7 January 1984: 10–13; Productioncars.com, Book of Automobile Production and Sales Figures, 1945-2005 (N.p.: 2006); “Road Test: Ford Escort 1.3L,” Motor 3 January 1987: 10–15; “Road Test: Ford Fiesta 1.3 GL,” Motor Road Tests 1980: 162–165; Graham Robson, “Closing Time,” Classic Ford July 2006: 74–77, and “Lady Killers,” Classic Ford March 2002: 44–48; Ian Sadler, “Class of ’84,” Cars and Car Conversions September 1984, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 38–41, “Roadrunner,” Cars and Car Conversions September 1981, reprinted in ibid: 20–21, and “The Pretenders….” Cars and Car Conversions May 1982: 14, 81–82; Ian Sadler, et al, “Ford Fiesta: A EuroKid comes of age…” Cars and Car Conversions September 1980, reprinted in ibid: 5–11; David Scott, “Breakthrough in anti-skid technology,” Popular Science Vol. 229, No. 3 (September 1986): 93, and “Coming: skid control for small cars,” Popular Science Vol. 224, No. 1 (January 1984): 68–69; Werner Schrut, “Kölns Kleinster: Wie gut ist der neue Mini von Ford?” Auto Motor und Sport 14/1976 (7 July 1976): 32–42; Edouard Seidler, Let’s Call It Fiesta: The autobiography of Ford’s Fiesta (Newfoundland, NJ: Haessner Pub., 1976); Bob Segui, “The Last Healey,” Retro-Speed, n.d., www.retro-speed. co.uk, last accessed 1 November 2013; Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, “Energy Policy and Conservation Act,” Public Law 94–163, Title V (Part A – Improving Automotive Fuel Economy), 22 Dec. 1975; Keith Seume, “Rippy’s back!” Hot Car May 1981 [nn]; Andrew Shanks, “Plans for a Fiesta,” Autocar 17 July 1976: 20–21; Don Sherman, “The Econoboxes: All the small cars that are fit to drive, Part One,” Car and Driver Vol. 24, No. 1 (July 1978): 33–56; Dennis Siamanitis, “Ford’s New Escort: Some Technical Tidbits,” Road & Track Vol. 31, No. 11 (July 1980): 77–80; “Smalls of the Line,” CAR July 1990: 120–129; “Sonderserie Ford Fiesta Special: Erinnerungen an Monte Carlo,” Rallye Racing September 1979: 59; Ollie Stallwood, “Ford Fiesta 1.4i Style+ Auto,” Autocar 29 June 2009; “Star Road Test: Ford Fiesta S,” Motor 5 February 1977: 4–9; “T for 2,” Auto Performance October 1982: 81; Alexander Stoklosa, “2014 Ford Fiesta 1.6L S Sedan / Hatchback,” Car and Driver July 2013, www.caranddriver. com, accessed 4 November 2013; “Supersport [Part One],” Performance Ford December 1989, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 70–73; “Supersport: Part Two: Restoration,” Performance Ford January 1990, reprinted in ibid: 74–77; “Test Extra: Ford Fiesta 1.6S 3-dr,” Autocar & Motor 12 July 1989, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 59–61; “Test Extra: Ford Fiesta RS Turbo,” Autocar & Motor 20 June 1990, reprinted in ibid: 78–83; “Testing for fun,” CAR September 1990: 84–95; “Test Update: Second Chance,” Autocar 25 December 1985: 18–21; “The Autocar Road Test: Ford Fiesta XR2i 16V,” Autocar & Motor 8 July 1992: 36–39; Mark Theobald, “Tom Tjaarda 1934-present,” Coachbuilt, 2004, www.coachbuilt. com, accessed 18 May 2013; “The X Factor,” Cars and Car Conversions January 1980, reprinted in High Performance Capris Gold Portfolio 1969-1987: 101–102; “3 Car comparison test,” Popular Motoring May 1980: 38–41; the Tjaarda Design website, www.tomtjaardadesign. com/portfolio.html, accessed 18 May 2013; “Variable Appeal (Road Test: Ford Fiesta 1.1 Ghia Auto),” Autocar 20 May 1987: 42–49; David Vivian, “Ford Fiesta 1.6 TDCi,” Autocar 30 November 2004, “Ford Fiesta ST,” Autocar 23 November 2004, and “XR2i,” Autocar 15 February 1989, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 52–53; Ron Wakefield, “Ford Fiesta: Henry builds a minicar,” Road & Track Vol. 28, No. 2 (October 1976): 34–36; Gavin Ward, “Ford Fiesta,” Auto Express, 9 March 2004, www.autoexpress. co.uk, accessed 4 November 2013; Jeremy Walton, Escort Mk 1, 2 & 3: The Development & Competition History (Sparkford, Somerset: Haynes Publishing Group, 1985); “Ford’s FWD rally Fiesta with a 4-WD secret,” Motor Sport March 1979: 319–321, and “Tuning Topics: Promising Capri and Fiesta Developments,” Motor Sport April 1978: 440–444; Mark Wan, “Ford Fiesta,” AutoZine, 29 November 1999, www.autozine. org/ Archive/Ford/old/ Fiesta_1999.html, accessed 4 November 2013, “Ford Fiesta,” AutoZine, 20 January 2002, www.autozine. org/ Archive/Ford/old/ Fiesta_2001.html, accessed 4 November 2013, and “Ford Fiesta,” AutoZine, 29 September 2008 to 20 March 2013, www.autozine. org/ Archive/Ford/new/ Fiesta_2008.html, accessed 4 November 2013; Ian Wearing, “At last, a worthy sporting Fiesta,” Performance Car August 1990, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 95; Rory White, “Common Ford Fiesta problems,” What Car? 5 February 2013, www.whatcar. com, accessed 4 November 2013; Klaus Wießmann, “Aufwertung: Neues Modell mit 1,3 Liter 66 PS-Motor,” Auto Motor und Sport 22/1977 (26 October 1977): 108–112; “Wild Bunch (Group Test: Ford Fiesta XR2, MG Metro Turbo, Peugeot 205 GTi),” What Car? August 1984: 40–44; www.fueleconomy.gov, last accessed 16 January 2017; “Year of the Fiesta,” Rally Sport March 1979, reprinted in High Performance Fiestas 1979-1991: 12–15, 19; and Stephan Zander, www.fiesta1.de, last accessed 5 November 2013.

Some additional information on the Fiesta’s antecedents and leading rivals came from “A curious move in car-engine design,” New Scientist Vol. 15, No. 306 (27 September 1962): 663; Keith Adams and Ian Nicholls, “The cars: Mini development history, part 1,” AROnline, 5 August 2011, www.aronline. co.uk, last accessed 18 June 2013; the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, Cars That Never Were: The Prototypes (Skokie, IL: Publications International, 1981); “AutoTest: Ford Escort 1100 3-door,” Autocar 27 September 1980: 36–39; “AutoTest: Ford Escort 1.3 Ghia (1,297 c.c.),” Autocar 22 March 1975: 47–51; John R. Bond, “Which Way Our Car? Part II: The Cardinal, Ford’s New Small Car,” Car Life Vol. 9, No. 6 (July 1962): 60–61; “Giant Test: Ford Escort 1.3GL -v- Opel Kadett 1.3S -v- VW Golf 1.3LS,” CAR December 1980: 62–68; “AutoTest: Ford Escort 1300 Ghia 5-door,” Autocar 27 September 1980: 30–35; “Escort Mexico,” Autocar 10 December 1970: 47–49; “Brief Test: Escort 1100L,” Motor 8 March 1975: nn; Arch Brown, Richard Langworth, and the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, “1959-1997 Austin/Morris Mini,” Great Cars of the 20th Century (Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, Ltd., 1998): 278–281; Roger Carr, “Car Carshow Classic: 1960 Austin Seven (Mini) – The Future Started Here,” Curbside Classic, 16 December 2014, www.curbsideclassic. com/ curbside-classics-european/ car-carshow-classic-1960-austin-seven- the-future-started-here/, accessed 16 December 2014; “Ford Escort: 40 Years,” Ford Anniversaries 2008, Ford of Europe, www.fordmedia. eu, retrieved 10 January 2010; “Ford Anglia 1200 Estate Car 1,198 c.c. (Autocar Road Test No. 2040),” Autocar 13 August 1965: 303–308; “Ford OSI 20m TS Website,” n.d., www.osi20mts .com, accessed 18 May 2013; the German-language classic Ford Taunus website, www.fordtaunus. de, accessed 7 June 2013; “Ford Taunus 12M(P4),” Classic & Sports Car, 28 March 2011, www.classicandsportscar. com, accessed 25 May 2013; “Group Test: Austin Allegro 1100, Fiat 128, Ford Escort 1300 XL, Honda Civic,” Motor 20 October 1973: 54–60; “Giant Test: Austin 1300 Super De Luxe, Ford Escort 1300 Super, Hillman Avenger Super, Vauxhall Viva SL,” CAR July 1970: 62–69, 87; “Giant Test: Fiat 127DL, Renault 5TL, VW Polo N,” CAR August 1975: 48–56; “Giant Test: Ford Escort 1.3GL -v- Opel Kadett 1.3S -v- VW Golf 1.3LS,” CAR December 1980: 62–68; “Giant Test New Car Analysis 3: Escort 1300L, Avenger S1600, Renault 12TL,” CAR April 1975: 62–69; “Giant Test: Renault 11GTL -v- Austin Maestro 1.3L -v- Ford Escort 1.3GL,” CAR September 1983: 106–113, 119–120; “Giant Test: Toyota 1000, Fiat 127, Mini 1000,” CAR February 1975: 68–74; David Knowles, MG: The Untold Story (Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1997); Richard M. Langworth, The Thunderbird Story: Personal Luxury (Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1980); John Lee, “1953 Oldsmobile Fiesta: When the Dream Came Alive….” Special Interest Autos No. 106 (July-August 1988): 36–41, 65; Brian Long, Porsche 914 & 914-6: The Definitive History of the Road & Competition Cars (Dorchester, Dorset: Veloce Publishing Ltd., 2011); Paul Niedermeyer, “Curbside Classic: Austin Mini – Yesterday’s Mini, Today’s Micro,” Curbside Classic, 16 May 2011, www.curbsideclassic. com/ curbside-classics-european/ curbside-classic-1959-week-mini- yesterdays-mini-todays-micro/, accessed 16 May 2011; Jan P. Norbye, “False Starts and Second Guesses,” Special Interest Autos No. 54 (December 1979): 20–25; “Penny-a-mile Motoring Part I,” Autocar 6 April 1974: 24–29; Pew Environment Group, The, “History of Fuel Economy: One Decade of Innovation, Two Decades of Inaction,” Pew Charitable Trusts Clean Energy Program, April 2011, www.pewtrusts. org/~/media/ assets/2011/04/ history-of-fuel-economy-clean-energy-factsheet.pdf, last accessed 15 January 2017; “Preise der neuen VW-Modelle Jahrgang 1977,” Auto Motor und Sport 16/1976 (6 August 1976): 14; Chris Rees, Essential Ford Capri: The Cars and Their Story 1969-87 (Bideford, Devon: Bay View Books Ltd., 1997); “Road Test: Ford Escort 1.4GL,” Motor 29 March 1986: 10–13; “Road Test: Ford Escort Sport 1600 2-Door,” Motor 8 March 1975: 2–7; Graham Robson, Cortina: The Story of Ford’s Best-Seller, Second Edition (Dorchester, Dorset: Veloce Publishing Ltd., 2007); Graham Robson and the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, Volkswagen Chronicle (Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, Ltd., 1996); Heinz P. Schlichting, “Road Testing Ford’s Cardinal,” Popular Mechanics Vol. 118, No. 6 (December 1962): 84–87; LJK Setright, “Fly Babies,” CAR April 1980: 66–70, and “Will there ever be a better mini than the Mini?” CAR May 1992: 90–97; Mary Wilkins and Franck Hill, American Business Abroad, Ford on Six Continents (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1964); and “Wizardry on wheels” [advertisement 9/13R], The Motor 2 September 1959: 46–47.