THE XP-784 TAKES SHAPE

Since the E-car project now involved three divisions — Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac — planning and development was coordinated and overseen by the central Engineering Staff, then headed by VP of engineering Harry Barr. By early 1964, the divisions were allowed to go forward with their own production engineering work, although development of some major systems would be shared between the three divisions, Fisher Body, and (as alluded above) the Saginaw and Hydra-Matic Divisions.

Although GM stylists had described North’s design as “the monocoque look” for the way the sail panels flowed seamlessly into the rear deck and fenders, the production car would be another of GM’s exercises in semi-unitized construction. Harold Metzel was not a fan of full monocoque construction, which transmits more noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH) than does a rubber-isolated separate frame. The XP-784’s body structure, designed by Fisher Body, would be essentially unitized, but to reduce NVH, the engine and front suspension were carried on a partial frame whose trailing ends carried the front shackles of the rear springs. Oldsmobile was not entirely satisfied with this solution, which was actually devised and developed by Cadillac, so the second-generation Toronado (launched for the 1971 model year) would adopt a full perimeter frame instead.

The rear suspension, also developed by Cadillac, used a beam axle on single leaf springs (comparable to those used by the Chevy II/Nova) along with four tubular shock absorbers. Two were mounted vertically in the conventional fashion, but the other two were mounted horizontally, above and parallel to the rear springs, allowing them to do double duty as radius rods.

The XP-784 front suspension was a typical double wishbone arrangement, but the halfshafts made conventional lower-arm-mounted coil springs impractical. Oldsmobile considered mounting the coils atop the upper wishbones, à la Nash Rambler, Ford Falcon, or Thunderbird, but finally settled on longitudinal torsion bars like those used by contemporary Chryslers or the old GMC L’Universelle. There was also a front anti-roll bar. Steering was by power-assisted recirculating ball with a variable ratio of 17.8 to 19.4:1; an additional shock absorber mounted on the steering linkage served to damp steering kickback.

To better amortize the substantial development and tooling costs, Cole wanted all three divisions to share this layout and the UPP, each substituting their own V-8 engines. Cadillac agreed, but asked for and received an additional year for styling and mechanical development; Oldsmobile had a substantial head start in both areas. Buick general manager Ed Rollert, however, said no to front-wheel drive. Problems with untried technology had done Buick great harm in the late fifties, and we suspect Rollert was not eager to go down that road again. Cole eventually agreed to allow Buick to adapt the chassis and cruciform frame of the 1963–1965 Riviera to the new E-body shell, retaining rear-wheel drive.

THE 1966 OLDSMOBILE TORONADO

The XP-784 still didn’t have an official name when road testing began in late 1964. Early press reports speculated that the car would be called “Holiday,” a designation Oldsmobile had used for its pillarless hardtops since 1950. In fact, leading contenders included Cirrus (a name later adopted by Chrysler), Scirocco (later used by Volkswagen), and Magnum (later used by Dodge). Chevrolet general manager Bunkie Knudsen finally offered the name “Toronado,” which Chevrolet had registered for an undistinguished 1963 show car.

The 1966 Oldsmobile Toronado was officially announced in late July and went on sale September 24, 1965. It attracted considerable attention from the automotive press, which hailed it as the most interesting domestic car since the 1963 Corvette Sting Ray. The Toronado promptly won Motor Trend‘s 1966 Car of the Year Award and Car Life‘s 1966 Award for Engineering Excellence.

Testers were surprised to discover that the Toronado’s front-wheel drive was almost undetectable on the road. Despite the big V-8’s ample torque, there was no perceptible torque steer or steering kickback. With just over 60% of the car’s static weight on the front wheels, understeer was the order of the day, but contemporary testers didn’t find it excessive, at least compared to other large American cars of the time. Unlike a RWD car, however, it was impossible to bring out the Toronado’s tail with the throttle, and the Toronado had almost none of the Mini Cooper‘s penchant for lift-throttle oversteer. As advertised, the Toronado’s high-speed stability was excellent and testers who had the opportunity to drive it in the rain found that the Toronado’s wet-weather traction was indeed superior to the RWD Riviera’s.

If the Toronado’s handling was a mostly pleasant surprise, its stopping power was not. Testers from Autocar, Car, Car and Driver, Car Life, Consumer Reports, Road & Track, and Road Test all found the Toronado’s brakes inadequate, reporting lengthy stopping distances, substantial fade, directional instability in panic stops, and a tendency to lock the lightly loaded rear wheels. Both Car Life and Car and Driver took issue with Oldsmobile’s contention that the Toronado didn’t need discs; Car Life recommended also adding a pressure-limiting proportioning valve, like that of the contemporary Ford Thunderbird, to delay rear-wheel lockup.

Brakes aside, the Toronado was a remarkable piece of engineering. No less an authority than Alec Issigonis, BMC technical director and designer of the Mini, had declared that front-wheel drive was impractical with engines over 2 liters (122 cu. in.), but the Toronado coped admirably with 6,964 cc (425 cu. in.), 385 gross horsepower (287 kW), and 475 lb-ft (644 N-m) of torque. For all its novelty, the Unitized Power Package also proved to be remarkably reliable. The production line — established in a separate building from other Oldsmobiles — had its issues early on, but there were few problems with the powertrain in service.

Although the FWD powertrain was relatively trouble-free, several sources claim the Toronado was prone to engine fires due to elevated under-hood temperatures and issues with the Rochester Quadrajet carburetor, which sat 1.2 inches (30.5 mm) lower than on RWD Oldsmobile engines. We found no hard data on Toronado engine fires, but GM later admitted that some early Quadrajets — though not specifically those used by the Toronado — had defective fuel inlet plugs that could cause fuel leaks and potentially start an engine fire. In the seventies, that issue became the subject of a lengthy court battle between GM and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which ordered GM to warn owners of Quadrajet-equipped ’65 and ’66 Chevrolets and Buicks of the fire danger. GM’s own affidavits linked the defective plugs to more than 650 engine fires, a number the NHTSA insisted was conservative. Rochester later redesigned the inlet plugs, and some owners and restorers substituted aftermarket plugs or sealed the plugs with epoxy to avoid leaks.

Perhaps the most remarkable demonstration of the UPP’s durability didn’t involve a Toronado at all. In the summer of 1965, John Beltz, stung by pre-launch skepticism about the UPP’s unusual chain drive, commissioned Jack “Doc” Watson of Hurst Performance Products to develop a Toronado-powered drag racing exhibition car. The result was the “Hairy Olds,” a 1966 Oldsmobile 4-4-2 powered by two complete Toronado drivetrains, giving it four-wheel drive. Each of the two engines was bored out to 432 cu. in. (7.1 L), fuel-injected, and fitted with a GMC 6-71 supercharger; together, the two supercharged made than 1,000 horsepower (750 kW).

The performance of the Hairy Olds, which made its debut in Bakersfield, California in March 1966, was spectacular in every sense of the word, although it was not easy to drive; Watson said it had substantial torque steer at both ends. The Hairy Olds was sidelined by engine failure in 1967 and subsequently destroyed by Hurst, although an Oldsmobile club created a faithful replica in 2002.

The Toronado was also the basis of several other custom cars, including a Dean Jeffries special built for New Orleans Saints owner John Mecom, Jr., featuring extended front fenders and a grille transplanted from the Dodge Charger; a quartet of stretched-wheelbase “67-X” cars built by George Barris for an Imperial Oil contest; a unique Toronado convertible, designed by George Barris for the TV series Mannix; and a number of Toronado limousines. Oldsmobile’s Engineering Shops also created a single short-wheelbase Toronado emergency vehicle, shortened by 52 inches (132 cm) and fitted with a single seat, wooden bumpers, and a spotlight.

My parents owned 73, 75, and 79? Toronados and loved them all.

I bought a 74 Toronado 455 from a junk yard and drove it for several years and many miles. I don’t remember the brakes being poor, but it was a monster of a car; the hood was a mile long. It was one of my all-time favorite cars.

Interesting memories:

Mine was an dual airbag car. GM offered it as an option for a couple years, before it disappeared for +20 years.

The ride was so smooth, I blew a rear tire and never realized it until ALL the rubber was gone and I was running 60mph on the rim.

I probably owned it for a year before I “burned rubber”. OMG! The torque steer was almost uncontrollable! I was amazed by the tire smoke curling over the front fenders.

Great story! I would love to find such a car today. The airbags made it super rare too, only about 10,000 cars were made with those over three years. That’s not just Toros, but over all of Cadillac, Olds and Buick-about 9 models in total.

The story abot blowing a tire at speed is impressive! In a way, I would love to exprience something like that in a car.

I had a 1966 Toronado and do not remember any torque steer at all since Olds used unequal half shafts to control it. I also had a 2000 Eldorado with a transverse mounted engine it suffered horrible torque steer. But the 66 Toro had drum brakes that after some moderate fast driving in neighborhood streets, the pedal became hard and you virtually had no brakes until the drums cooled. Brake fade.

Loved both cars though.

The Unitized Power Package from the original Toronado and FWD Eldorado really didn’t produce much if any torque steer. Brake fade, though, was another matter. Weight distribution was a big part of the problem. The brakes were the same as a RWD Oldsmobile 88, but there was a lot more weight on the nose, which would dump more heat into the front drums than they could manage while unloading the rear wheels and allowing the rear brakes to lock prematurely.

I have a 92 red Trofeo that I bought new in April of 92 after two years searching for the perfect car. It is just getting ready to turn 70,000 miles………and is still the most beautiful car I have ever seen.

I’m a kind of car nut, constantly looking at new models…….but nothing has come close to my Toronado in terms of aesthetical beauty.

I have two 92 Tornado Trofeos and both of them will not start after running for awhile. I have to wait about 30 minutes for the car to cool down before it can be started again. Otherwise I love the car and put up with it. If there are any fix its I would like to know about it.

I had that issue with a brand new one , on the third try from the Olds Dealer they finally figured out it was the electric fuel pump in the gas tank. At the point of the third repair I was hoping they would miss the problem again as we had a lemon law in NH if they failed the third time it was either a new car or my money refunded. But it never gave me the fits again,

Olds built two front wheel drive prototypes (using Corvair bodies) with an over-square 60 degree V6 engine transverse mounted, and automatic transmission. By the time we had these things running around, the F85 dressed up as a Cutlass was selling like hotcakes, so the idea of a small fwd car faded. I drove one of the cars once or twice, as it was being used as a utility car at the time. When Buick developed the 215 aluminum V8 into the iron V6, Olds wanted to use their own aluminum V6 from the fwd for the ’64 F85, but Buick won out and Olds had to use the Buick V6 as a base engine. I saw one of these Olds V6 engines sitting on the floor a couple of years ago at the Reo/Olds museum and no one there even knew what it was.

We built up the first Toronado prototype was using a production Buick Riviera that we modified for the fwd package.

This is a message to W. Thomas. Did you work in engineering at Oldsmobile? If you did which projects did you work in or on? I would suspect that you have plenty of interesting stores to tell! Now is the time to pass this on so it will not be forgotten. I am active on classicoldsmobile.com a web forum for Olds owners.fanatics. You may already be aware of that site but just wanted to pass on the info that will be read by many should you care to have some interest in your work experiance in Detriot.

Thank you,

Regards,

T. Ryan – Owner of a few W31s.

John Beltz was a real class guy. Died early from a brain tumor I think.

Interesting! I knew that Olds had a V6 prototype, but I didn’t know it was aluminum, as well.

John Beltz was definitely an interesting guy. John DeLorean later described sitting next to Beltz in a big group meeting with senior management; Beltz turned to DeLorean and whispered, “I wouldn’t hire any of these guys to run a [i]gas station[/i].” They were of like minds in that.

I’m not sure what kind of cancer John Beltz had. One source I saw made it sound like it was prostate cancer, but whatever it was, it spread very quickly. A sad thing.

Olds had an experimental iron V6, probably in 1948 or 1949. Looked just like the 303, same style heads and valve covers, manifolds, etc. Might have had a balance shaft in it, everyone back then thought a V6 needed one. Don’t know whatever happened to all those old experimental engines.

The aluminum V6 was a 60 degree engine, a small and narrow package, very modern, and as I said was very over-square – big bore and very short stroke. One of the engines we evaluated in our development was a Lancia V6. A nice engine too, but not as nice as the Olds. The Buick V6 was a 215 V8 cast in iron without the front two cylinders. We had a early prototype for test, from Buick I think, but maybe we at Olds built it up. Anyway this prototype was a cast iron 215 V8 with nothing in the front two cylinders. Cheap and easy, just cast a V8 in iron. This is a 90 degree block. At the time no one thought that a 90 degree V6 would work because of the uneven firing. Today there are big diesel 90 degree V6 engines.

For the Toronado transmission drive, we first tested timing belts instead of the chains that were eventually used. The belts were quieter and didn’t require lube, but belt life was a question.

long time ago…

[quote]Olds had an experimental iron V6, probably in 1948 or 1949. [/quote]

Was that the three-liter engine Charles Kettering developed to test the benefits of high compression ratios? I recall that there was an experimental engine running 12:1 CR, too high for any pump gas at the time.

Too bad you neglected the last Toros…

My daily driver is a 1990 Trofeo, and it is as fun to drive as the Alfa 164 I had! 28 mpg in mixed driving, too.

And folks still say it was GMs best looking car that year…

The second part of this story, coming soon, will talk more about the later Toros.

My best friend was an ASE Master tech, and he owned an immaculate 1980 Toronado that came with the 350 Oldsmobile engine.

He put in a rebuilt 403, but it came with a piston slap… so he “dropped in” a high-compression 455 from a wrecked late-60’s 98.

Of course, he had many problems to overcome, but he was an extremely skilled fabricator. By the time he got done, the 455 was running Holley ProJection, a modified ’74 HEI distributor, 2.5″ exhaust from a diesel, a fake catalytic converter, and about its ninth or tenth ‘strengthened’ TH325 transmission (sending torque through the fifth or sixth differential). I found him a set of heavy torsion bars from a diesel Eldorado, and an Eldo Touring Coupe donated its swaybars and rear springs. We had to put a steel T-brace to tie the front of the powertrain down: otherwise, the AC compressor would pop up high enough to lift the hood.

This car was [b]ridiculous.[/b] Dry roads were like rain-slicked pavement; damp roads were like glare ice, and snow? Forget it! It was capable of hiding itself in a cloud of tire smoke, and it would chirp the tires when floored at 60+ mph. At highway speeds, he could actually warn the passenger “Brace yourself: I’m gonna bounce your head off the headrest…” and, even though they tried to hold still, flooring the pedal would cause their head to snap back like a rear-end collision.

[quote=w. thomas]For the Toronado transmission drive, we first tested timing belts instead of the chains that were eventually used. The belts were quieter and didn’t require lube, but belt life was a question.[/quote]

In one of his “Miscellaneous Ramblings” columns, [i]Road & Track[/i] editor John R. Bond said he thought it was pertinent that the Toronado wasn’t offered with a stick shift. He speculated that snap shifts would have been rough on the Hy-Vo chain.

While this may have been true, my 2 cents is that the typical Toronado buyer probably would have preferred automatic anyway.

Only similar drivetrain layout I can think of (longitudinal engine, transmission alongside engine, chain drive) would be the Saab 99 and early 900. But Saab turned the engine end for end to put the flywheel in front.

Oldsmobile engineers told [i]Car and Driver[/i] that they were still not confident a manual gearbox would work with the UPP. The torque converter played an important role as a vibration and shock damper, as well as acting as a fluid clutch. Even if it didn’t present chain durability problems, a friction clutch and manual gearbox may have been hard pressed to provide acceptable levels of NVH. (It’s worth noting that reviewers of the original Pontiac Tempest, with its big slant four engine, found that it was notable smoother than the manual-shift car, for much the same reason.)

But yeah, even if they had gotten a manual gearbox to work, it’s hard to see many Toronado buyers caring, even as a no-cost option. In terms of flexibility, the Turbo Hydramatic didn’t give up very much to a four-speed, in any case. Breakaway multiplication (torque converter x low gear) was 5.46:1. The switch-pitch converter acted as a sort of 3.5-speed transmission; the stator pitch would change when you stabbed the throttle, providing a torque boost without an actual downshift (which was also available if you pressed hard enough to trigger the kickdown). A well-ratioed four-speed might have given better acceleration in the 0-50 mph range, but not enough to make buyers in that class want to shift for themselves.

The Strato bucket seats were a no-cost option on the Toronado Deluxe from 1966 to 1970. For 1966-67, cars so equipped could also be ordered with a short consolette with storage compartment as could the Eldorado and Riviera (latter also available with a full shift console). The 1968-70 Toronado Deluxe models with the bucket seat option could be ordered with a full center console that included floor shifter and storage compartment. That console was nothing special as it was the same one found in bucket-seat equipped Cutlass Supreme and 442 coupes, and the full-sized 67-68 Delta 88 Custom and 69-70 Delta Royale coupes.

While bucket seats were considered a very important part of the personal-luxury image of most such cars (i.e. Grand Prix, Thunderbird), they just weren’t very popular among Toronado (or Eldorado)buyers due to the front-drive, flat floor configuration, so the Strato bench seat was the most popular for both cars. Riviera also went to a standard bench seat with the ’66 models, which turned out to be more popular than the optional buckets and Ford made a bench seat standard on the ’68 T-Bird in response to the popularity of such seats in Riviera, Toronado and Eldorado.

The 1971-78 Toronados didn’t offer any bucket seat option, just a standard notchback bench or optional 60/40 bench in cloth or Morocceen vinyl, with velour added for 1974. Sportiness was out and Brougham-style luxury was in – with the base model now called the Toronado Custom (trim same as previous Deluxe models) and the uplevel was now the Brougham. Due to the slow sales of the original Toro, Oldsmobile chose the ’67-70 Eldorado for the styling direction of the second-gen Toro while the flagship Caddy got boxier styling with opera windows and a convertible – and Buick went wild with the boattailed Riviera.

Although the ’71 Toronado still came with the 455 Rocket as standard power, it was considerably detuned as part of GM’s mandate that its engines be designed for regular leaded or unleaded gasoline.

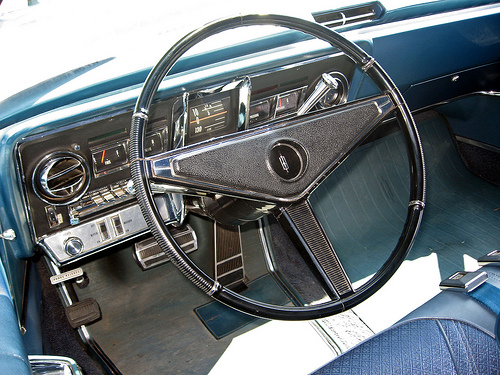

It’s interesting to note that while buckets were a no-cost option on the Toronado deluxe, they were [i]not[/i] free on the Eldorado — Cadillac charged $184 with leather, or $292 with cloth (as a special order). As the interior photo in this article indicates, with the Deluxe interior’s upholstery design, a Strato-Bench with the armrests folded down looks like buckets at a casual glance. Since most contemporary buckets aren’t any more supportive than that anyway, there wasn’t much reason to switch.

The installation of bench seats in the Thunderbird was only partly in response to market trends. Until the 1967 model, bench seats had not really been possible with the four-seat Thunderbirds from a structural standpoint. The ’58-’66 unitized T-Birds had a very prominent driveshaft tunnel, which also served as a structural spine. Since there was no hiding it, the Thunderbird design team decided to decorate it and turn it into an interior styling feature. The ’67 models went back to body-on-frame construction, so the tunnel was no longer any more prominent than any other RWD car; since there was also the Landau sedan, a bench seat made sense. However, the Thunderbird design team also said they had essentially exhausted the possibilities for the previous interior treatment, which had been so widely imitated. I think it’s likely they would have gone for six-passenger seating, even if GM had not.

We’ll talk more about the styling and features of the second-generation Toronado in part two. It’s worth pointing out that the trend toward Eldorado styling was apparent even in 1970, the last year of the original body. I don’t have a rear three-quarter shot of the 1970 Toronado, but if you look at the rear fender treatment and the reshaping of the rear fenders, it definitely looks like they were straining for an Eldorado look. I’ve reached out to some contacts to see about getting more specific information on the design process of the ’71 Toronado.

During this time, Pontiac claimed that its Morrokide vinyl upholstery had the “look and feel of top quality leather” but with far more durability and practicality for everyday use. The Wide-Track people during this time only used leather on the top-line Bonneville convertible through 1965 (from 1966 to 1970 only when the Brougham option was ordered) and as a $199 option on the 69-70 Grand Prix but wasn’t very popular so it was dropped for 1971.

The early 1970s set an all-time low for the use of leather upholstery in American cars. In 1972 you could count fingers on two hands all the cars that still offered real hide either as standard or optional and several makes didn’t offered leather on any model including American Motors, Plymouth, Dodge, Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Buick.

Only the luxury makes including Cadillac, Lincoln and Imperial offered it on most models while the lesser makes only on certain flagships including Chevrolet (Corvette), Ford (Thunderbird), Mercury (Cougar XR-7), and Chrysler (New Yorker).

The Toronado section of the ’67 Oldsmobile full-line brochure shows a photo of an all-vinyl bucket seat with the sentence “If you think buckets are basic, these tailored Morocceen upholstered bucket seats are available at no extra cost on Toronado Deluxe.”

I also have the ’66 Olds full-line brochure on which the listing of popular options on all model lines on the back cover. The one for “Strato bucket seats” states under the Toronado heading as “Optional”.

Also note that while Eldorado offered bucket seats as an expensive extra-cost option in either cloth or optional leather, Toronado only offered them in all-vinyl or possibly cloth-and-vinyl as did Riviera, while T-Bird offered buckets with vinyl, cloth or leather.

The Eldorado’s most direct competitor, the Continental Mark III introduced in 1968 did not offer bucket seats as an option or otherwise. Only seating choice was a Twin Comfort 50/50 bench with dual armest in cloth or leather. Just as Eldorado shared body/chassis with Riviera and Toronado, the Mark III used the Thunderbird base.

In addition to the front-drive flat floor of Toronado and Eldorado, probably another reason that bucket seats were become increasingly passe were the emergence of even sportier personal-luxury cars based on intermediate platforms such as the Pontiac Grand Prix and Chevrolet Monte Carlo, which were lower in base price but could be similarly optioned in plushness and power.

I haven’t done a detailed study of Toronado interiors, but some contemporary reviewers, notably [i]Car Life[/i], were not terribly impressed with the Toronado’s interior materials, either stylistically or in terms of quality. [i]Car Life[/i]’s reviewer felt that leather upholstery would have been more appropriate for the first Toronado’s GT character, and wondered if Oldsmobile had cut corners on the interior to make up for the cost of the drivetrain.

Toronado interiors on the early models were no better or worse that that of Riviera or T-Bird, or even other Oldsmobiles – and pretty much on par with the C-body Ninety-Eight. Possible that the tester was comparing the Toro’s interior to that of the Thunderbird’s “rolling jukebox” full of gadgetry or the 1963-65 Riviera’s dash with round instruments, brightwork and walnut trim. Both of those cars had 4-place cabins with bucket seat/console interiors.

A friend’s dad had a 66 and a 70 Toro. The 66 was a very impressive car, although I never drove it or the 70 model. I thought the 66 was and is one of most beautiful cars ever. The 70 looked a prehistoric beast and was just ug-lee. It’s a shame that Olds felt it had to make the Toro styling just as boring as the rest of the line, which traditionally had about as much flair as a top-loading washing machine. They screwed up the Aurora too by making a (surprisingly) lesser copy as a Riviera and diluting the cachet the car had for a brief while. I did drive an Aurora and it was one of better 90s American cars I’ve experienced. The Olds staff never seemed to lack for imagination but it seems they were always stifled by clueless division and GM management.And then they wondered what happened…

Well, ‘clueless’ needs some qualification. While the Oldsmobiles of the seventies didn’t win a lot of critical acclaim for their styling, they were amazingly successful. Olds displaced Pontiac in the number-three sales slot in 1972, and held on to that position in 1973 and from 1975-1981. (They lost out to Plymouth in 1974, thanks mainly to the OPEC embargo.) By 1977, they were consistently selling more than a million cars a year. The second- and third-generation Toronados, while never a big hit, sold a lot better than the original. So, while I don’t care much for the aesthetics personally, it certainly worked commercially. Whether they would have maintained that success into the eighties if not for the dramatic loss of autonomy under Roger Smith, though, is an interesting question.

I thought Olds Aurora was one of the better riding front drive cars with the strut suspension

The fourth-generation Toronado introduced in 1986 was a sales disaster due to a drastic downsizing to near-subcompact dimensions (in comparison to generations 1 and 2, and still much smaller than the “downsized” 79-85 models which were mid-sized). It did have more common styling to other Oldsmobiles such as the split grille (with hidden headlights for first time since ’69)but looked way too much like a Cutlass Calais that sold for half the price.

The ’86 Toronado (along with Riviera and Eldorado) were designed in 1981 when gasoline prices were $1.50 per gallon and rumors of $2 to $3 per gallon gas by 1985 were running rampant so GM pushed the panic button and made plans to drastically downsize all of their cars including the C-body luxury models and the B-body full-sized family cars – both of which also courted disaster when their front-drive replacements appeared due to the fact that gas prices had dropped to around $1 per gallon and Americans weren’t “thinking small” and went back to larger cars.

Production for 1968-70 W-34 optioned Toronados:

1968: 111 (NOT 150, as mentioned in this article)

1969: ?

1970: 5,341. 1970 W-34s were referred to as GTs.

0-60 times was about 7.5 seconds

On a good day, quarter mile times were about 14.7 sec @ 97 mph.

1968 w-34 only had the “Force Air-Induction” and radiator switch 1968 and 1970 W-34s had a notched rear bumper, 1969 did not.

All W-34s have a OM transmission code and dual exhaust. Most 1968-70 Toros are/were single exhaust, when these E-Bodies left the Lansing factory.

Jerry,

If you look back at the text, it does not say there were 150 W34 cars in 1968; it says there were [i]fewer than[/i] 150. I’ve seen at least two sets of conflicting figures — one was 124, one was 111. Since I didn’t have a definite total, I said "fewer than 150," just to illustrate the general magnitude of production (i.e., not a lot).

Automotive Mileposts quotes 2,844 for 1969 W34 production. I don’t know what their source was.

I was a 10 year old car nut in 1965 when the Toronado was introduced and my parents were “Oldsmobile people”, so I followed all the news about the Toro. I remember very well the reports of the many underwhood fires in ’66 Toronados. I don’t remember the cause, but there was a recall to correct it. I tried in vain to get my parents to buy one, but in addition to having only two doors, they thought it was ugly. I still think it’s one of the best-looking cars ever made.

I’ve heard various anecdotal reports of Toronado engine fires, but I wasn’t able to find any hard data on recalls, etc. — if you know of any specific sources, please let me know!

Good to have you back writing new content, Aaron! Your work is in my opinion incomparable, and has been missed.

The comparison of the Toronado to the Riviera is slightly askew from the more directly similar Cadillac Eldorado, which used the same GM front wheel drive system, whereas Riviera comparison leads to Thunderbird, Lincoln Continental Mark cars, and then in ’67, even the larger intermediate AMC Marlin.

It’s true that Buick rejected front-wheel drive for the Riviera until the late 1970s, but the Riviera, Eldorado, and Toronado all shared the same E-body shell. It would be reasonable to describe them as fraternal triplets; not identical, but closely related.

Although the Toronado was not that mechanically similar to the Riviera, the need to share the latter’s body shell strongly influenced its design, particularly its overall size. Their overall dimensions are nearly identical. They were also direct competitors; the Toronado was actually a few hundred dollars more expensive than the Riviera, but their "fully equipped" prices were very similar.

All the personal-luxury cars were intended to compete in the same market segment as the Thunderbird. The Eldorado and Continental Mark were aimed at a richer buyer, of course, but they were conceptually similar to their less-expensive brethren. The Eldo, naturally, was very similar to the Toronado, whereas the Continental Mark III was derived from the Thunderbird.

Thanks again for another great article.

I owned a 66 Toronado. It was indeed a stunning car to look at. The brakes, however, were hair-raisingly bad. What for a modern car was just a normal stop could become a standing on the pedal and pray longest moment of your life count your sins event.

How they could allow this design to be produced is beyond me. And yet, its sheer massive sculptural beauty compelled me to hang on to it for many years.

The Oldsmobile engineers were aware that the brakes had their work cut out for them — that’s why they had finned drums and the slotted wheels — but I’ve never heard a convincing answer as to why they didn’t use discs, at least in front. The Toronado was an expensive car, so cost wasn’t as pressing an issue as on an A-body. A set of Corvette discs all around would have made the Toronado a lot more reassuring to drive.

the la salle II show cars mentioned in the article- the 2 seat roadster and 4 seat/4 door hardtop- were both configured as f/r drivetrain, not fwd. joe bortz is currently restoring the roadster, and i had this car in my shop recently to renew the brake system. i also inspected the hardtop car for reference on the many parts missing from the roadster. both cars have identical drivetrains and chassis features, except the roadster has rear coil springs while the longer hardtop uses rear leafs.

the drivetrains are very convincing from the outside. all aluminum DOHC V6 with direct injection. all aluminum automatic transmission with, very very short center section as if it was all to be driven from the torque convertor without bands or planetaries. conventional driveshaft goes to a chassis mounted differential with independent axle shafts, but the wheel hubs are mounted on a large beam that goes behind the differential to both sides, so it is not truly independent. all done with very elaborate castings and chromed accessories such as starter, axle tubes, injection lines, etc, but everything is completely for show only. engine and trans have no internal parts nor do they include any castings where cylinders, cam, valves, etc could even be placed.

i’ve owned many toros and eldos over the years, still have my ’66.

best regards

larry claypool

Thanks for the clarification!

Great site, can’t believe I’ve only just discovered it.

I have a question on the ’65-66 Starfire and Jetstar. Did they use a unique hardtop body? The straight through sill and deep C-pillar don’t match the 88 hardtop’s kickup and fastback C-pillars, or the 98 hardtop’s more formal look. And I can’t think of a Pontiac or Buick with the same roofline. Wondering if this was an interim solution to the lack of a personal luxury car, in the wake of the Riviera and T-Bird?

The whole body wasn’t unique, but the Starfire does have different sail panels than the 88 Holiday coupe. I don’t know about the roof panel itself; I’d have to look at them side by side. In any case, the concave backlight looks very similar to that of the ’65-’66 Pontiac Grand Prix, albeit again with different sail panels.

In those days, each division had an annual tooling budget, which gave the divisions a certain amount of leeway to create new exterior panels. How much each division could do with that budget depended on how many model lines they had and how they were spending their money. By the ’60s, the individual divisions didn’t generally have the resources to do a completely new body on their own (although there were some exceptions), but they did have enough to give certain models a unique roof or something like that. In some cases, two or more divisions would agree to split the tooling cost for some new panel they could both use; for instance, that’s what happened with the roof panel used by the 1969-70 Pontiac Grand Prix and Chevrolet Monte Carlo. Other times, divisions were ordered to share certain things, although until the ’70s and ’80s that was more the exception than the rule.

(I should note here that it’s also possible to modify a single set of tooling to produce several variations of the same panel; sharing tooling doesn’t necessarily mean that the resulting panels are identical or interchangeable.)

It’s important here to distinguish between personal luxury cars and specialty cars. The distinction parallels the distinction between Supercars like the Pontiac GTO and sporty cars like the Firebird; one is a suitably massaged standard body shell, the other a unique body. You can make a standard car into a personal luxury car of sorts by giving it some unique styling details and dressing up the interior, which is what GM’s divisions did in the early sixties. The Thunderbird, however, was a specialty car: It had its own body shell not shared with anything else (other than some non-obvious commonality with the Continental), so it looked unique. The GM divisions were initially reluctant to go that route because it was very expensive even by GM standards, but it finally became clear that it would take specialty cars to fight specialty cars. Hence, the E-body.

The Jetstar I was a different story; its main target seems to have been the Pontiac Grand Prix. The Grand Prix was not exactly a Thunderbird fighter, since it was basically a Catalina with a different roof and trim, but it was very popular. Oldsmobile had had the Starfire since 1961, but the Starfire’s list price was a lot more than the GP, it arguably didn’t look as good, and it wasn’t marketed as aggressively, so it wasn’t a big seller. The 1964 Jetstar I looks like an effort to turn a Starfire into a Grand Prix fighter with less content and a lower base price. However, Oldsmobile muddied the water by introducing a new price-leader B-body with a similar-sounding name (Jetstar 88), plus the fact that a Jetstar I with a full load of options actually cost more than a Starfire. So, the Jetstar I was largely a flop and what units it did sell came mostly out of the Starfire, which wasn’t really very strong to start with.

I don’t think either was a Toronado stopgap per se — both the Starfire and Jetstar I were the sort of thing GM’s divisions routinely did anyway, often quite successfully.

I have already read several articles or books about UPP program and I wonder who initially was GM’s engineer which had the idea for this layout (fwd + transversely-mounted engine)? In addition, In the GM engineering journal on Olds Toronado, Andrew K. Watt told about a compact car with a more simplified design but stopped because Olds already envisaged a full-size car. I’d like too to know more infomations about that.

This is a great recounting of the First Toronado and it’s development. There were a lot of Oldsmobiles in my family back in those days, and an uncle bought one of the first Toronados in 1966. He had been a long time Pontiac man and was driving a Bonneville when my aunt had to go to the hospital for an operation. My uncle announced the need for a new car to my aunt in the hospital,and asked her what she wanted. She said, “Get one of those Toronado things,” and that’s what she got. He later got a 1970 Toronado.

Later, a friend’s young broth got a 66 or 67 (I can’t recall, as it has been so long now) with the optional 3.42 axle ratio. For such a heavy car, it was a veery potent machine.

One note to your excellent write-up, Aaron: the Toronado didn’t share exactly the same engine with the other models in 66 or 67. The Toronado 425 and the 400 that came in the 442 had special large 0.921″ lifters, which allowed more radical cams than the 0.842″ diameter lifters the other models’ engines received.

Thanks for a fine, well-researched article!

Thanks for the note — I knew the Toronado engine was a little hotter than the standard 425, but I didn’t catch that it had 4-4-2 lifters.

Sessler’s Ultimate American…….book has five tunes of Olds 425 cid in 1966 and 1967. Top tune is unique to the Toro.

Yes: The Dynamic and Delta 88 had the 2V version of the Super Rocket HC engine, which took premium fuel, but had a two-throat carburetor and single exhaust, giving 310 hp. A low-compression regular fuel version with 300 hp was optional, as were the 4V Super Rocket HC, with 365 hp, and the Starfire V-8, which as far as I can tell was the same as the L77 Police Apprehender engine — 4V, slightly higher compression, dual exhausts, 375 gross hp. The 4V Super Rocket was standard on the Ninety-Eight and optional on the Dynamic and Delta.

What ever happened to the 1967 X cars produced for an Imperial Oil contest.. where are they now?

Well written piece,lots of info that is new to me.

The Toronado “died” after the 1985 model year. GM’s E bodies for 1986 were major design disasters. It was downhill for GM until the corporation restructured after bankruptcy. Now it seems GM is actually interested in quality automobiles once again.

The first car I ever owned was a 1976 Olds Toronado. My dad bought it for me in 1982. Everyone else was driving around in little imports, the Prelude being the car of the day. They made fun of my ‘land yacht’. I never could parallel park the thing. But when youthful boasting got down to serious business and cars lined up on the pavement to have a go, true, most beat me off the line. But from 60 mph and up that big block ate those little rice burners alive!

I have never had a car with so much to give! It didn’t matter how fast you were going, if you asked it for more, it gave you more, never broke a sweat. Nowadays I get nervous if I have to pass a vehicle. In my Olds, heck, I’d whip out and blow past two at a time, never a worry, that speed was there! And it rode like a dream. I could jam 5 other people and we’d head out. Did our fair share of off-roading in it too.

It died when I hit a van and then drove under a semi with it in terrible snow conditions in BC’s mountains. The front of that car was mushed, but I still put it in park and turned it off and to the shock of all the witnesses, I stepped out of the car. Anything smaller and I would not have lived to learn what the internet is.

I bought my 2nd 1976 Olds Toronado several years later and loved driving it, but it had advancing rust and mechanical problems and husband was having fits over trying to find parts, so I sold the car. To my eternal regret. In my opinion no car has ever had that sexy look and cool appeal that the Olds Toronado had!

hello indeed inpresif story but i havean question

good morging I am Cees and living in Holland Have Toronado makeyear 1968 drove it in 1998 in Arizona and take ik Home to Holland. Last week a was working on the Toronado for the fist time and get it a live big problems ( of corse ) whit the fuel line Must totaly clean it out and get out pomp replace filter make al hoses clean. Well, it running now perfect but I have an queastion about the Boots of the axels of the 1968 Toronado two are broken so I must replace Boots on driveshaft rightsite

I can not find manual fot this action.

please somebody send or tell how to do en what to do. can i get out only the driveshaft or must i do more

Yesterday a start to work on the right front shaft axel to get it out it is lose but do not want to get out the upper and lower controle arm shock and olifilter are out now but still big problem must i lift it up? or must I remove one of the controle arms..

somebody knows the rigt way? thanks so far and greeting Cees

Cees,

I’m not qualified to provide mechanical or repair advice — sorry!

okee Aaron no problem ofcourse read some info in an Clinton auto repair manual book (1973-1980) but i think that is not the right info (newer Toronado) so must start looking again.

Cees,

It sounds like what you really need is an actual Oldsmobile shop manual that covers the ’68 Toronado. Where you’d come by one at this point I really don’t know — in the States, a big city public library might have one, but I don’t suppose that’s likely in the Netherlands. You might be able to find one to purchase online, I suppose.

Aaron Problem solved .. drive-axel is out must only get-out the starter the reason is that on the driveshaft there is an big balancer mouted in the middle of the axel.(of 10 cm wihte !!? ) so I can start repairing the BOOTS now. In the Clinton repair manual 1973-1980 the write only to get out the oilfilter.of the TORONADO . so I am happy now.. thanks for the support

My favorite US car of all time – to me the styling of the 1966 Toronado was beyond reproach. Also it was a technical tour-de-force.

I was an engineering student at the time and built the usual AMT model – it looked great in metallic blue. Then I discovered the General Motors Engineering Journal at our engineering library while looking for something else.

The Quarters 1 and 2 of 1966 go into the design of the car in great detail. Almost 20 years ago, I scored the 1966 GMEJ bound Annual, when the library dumped old “stock”. Other people got other years, darn!

The articles are written by all the people you mention in yours, but don’t answer any questions as to origin directly – they themselves say the XP-784 genesis and development are unclear up to the late 1950s and even beyond.

What is clear is the incredibly complicated organizational structure GM had in those days. Nobody in charge of anything except Mitchell in styling. So you had GM Central Office Engineering making UPP’s out of Caddy engines, and Oldsmobile Advanced Engineering making UPP’s for F-85, what they call a small car. Completely separate programs. Developing this and that apparently on whims. It wasn’t until 1962 until they sort of got together. Anyway, GM spent a whole chapter on organization in the EJ, so that the budding engineer reading this stuff could make some semblance of order out of the jumble of articles from different divisions, with nothing from Cadillac or Buick. Read it three times in a row, as I have this weekend, and you sort of get some idea of what transpired. Sorry, I’m not about to precis it here – too much, too complicated.

What is noticeably missing in your summary is that in fact Fisher Body made the Toronado from the cowl back, including all trim. They production-engineered the lot from drawings produced by Styling. The inner structure may be shared with the Buick, but you wouldn’t know it from this Oldsmobile had the subframe and engine to add to the Fisher production after the finished bodies were literally trucked from their plant in Euclid OH to Lansing for final assembly. The chapter is a dense 10 pages long as to how Fisher Body managed it, including the design of sheet metal drawing dies and window lifts.

The other noticeable thing is how much was optimized through computer-programming, and how much automatic machinery the General had, apparently haphazardly strewn all over the place, for durability testing. The left hand hardly knew what the right hand was doing – this comes across in the articles where someone or other will emphasize their group’s or division’s accomplishments, without mentioning anyone else! Nope, they’re on in the next article. It’s a bit of a hoot. Automatic welding stations, that we would call robots today, were also in evidence.

I highly recommend you read the Journal for 1966.

The only factual error I found in your article is that the fore-aft shock absorbers were mounted above, not below, the rear springs. But at the same time, much is missing from your summary. Finally, I’ll note that the engine had nowhere near 385 hp. A speed of 85mph in the quarter-mile even on a 4600 lb car suggest more like a so-so 250. These days, 290 hp in a 4400 lb MDX will get a less than 15 second quarter at well over 90 mph.

They sure are nowhere near, not even close, however, to this styling masterpiece.

Bill,

The easy parts first: You’re right about the horizontal shock mountings, so I’ve amended the text, and I agree that the Toronado’s net horsepower would probably be more in the realm of 250-270 hp. There are some dangers to comparing performance figures of modern cars simply because there are other factors involved (such as having more gears, better tires, and engines capable of maintaining a flatter torque curve over a considerably broader rev range), but there’s no doubt that Detroit’s gross ratings of this period generally had little direct relationship to actual, as-installed output. Also, I tend to suspect that with the early UPP/TH425 Toronado, a little less of the engine’s as-installed output made it to the drive wheels than would have been the case with an identical engine hooked to a conventional TH400 and RWD prop shaft. Still, lacking factory net output or drive-wheel horsepower figures, I’m left with the advertised output and the test figures.

For obvious reasons, it’s difficult for me to comment on sources I haven’t seen (and to which I definitely didn’t have access when this article was written). I would certainly be interested to see it if I’m ever able to. That said, even within the sources I did have, there was a lot of information I deliberately skipped or shorthanded in the interests of coherency or not further extending what is already a very long article.

As you observed in the engineering journal, the full story of any car produced by a company like GM or Ford involves the work of hundreds if not thousands of people in different divisions, departments, and work groups who don’t necessarily have — or care about — the bird’s eye view of the whole process. (One of the realities of any large organization is that people in each division or department are primarily interested in and accountable for their own group’s performance, regardless of how well the other groups are or aren’t doing.) That means a lot of granular detail in which to potentially get lost.

Obviously, with this or various other cars, people could write (and have written) entire books about the nuances of the development, engineering, or just the sort of fine technical points of concern to restorers. However, as a historian or an observer — even if you don’t have a fixed word count to meet — you have to ask yourself at some point, “Am I drawing a map or compiling an atlas?” I often feel like I tend toward the latter, so I’m occasionally bewildered (meaning no offense) when people point out all the things I’ve left out. I suppose this is what I get for having all these 10,000-word articles; one expects more than with a 500-word encyclopedia entry!

I have read these GMEJ articles and I felt too that GM’s engineers weren’t clear about UPP’s origin and its timeline. According to GMEJ, the La Salle II concept should have to get the first fwd tech but they didn’t tell if these prototypes should have used the DOHC V6 with fwd. I still wonder who was the first GM’s engineer to talk about front wheel drive? I could say some names like Charle Chayne, Charles Mccuen, Oliver Kelley or a ford transfuge but I have no certitude.

I have found an interesting testimony from a former gm’s engineer, Carl F. Thelin, which worked for GM Structure and suspension dpt (headed by Von D. Polhemus) on the fwd technology (http://cxsi.blogspot.be/2011/01/nih-factor.html).

Edmond — an interesting account I hadn’t previously seen. Part of the confusion, from my perspective anyway, is figuring out to what extent these projects were done by the corporate staff and to what extent they were done by the advanced engineers at the individual divisions. I assume the divisional engineers had access to the corporate projects at some stage (it wouldn’t have made much sense if they didn’t), but I don’t know how much the reverse was true. As far as I know, engineers in one division weren’t necessarily privy to what their counterparts in other divisions were doing at the same time unless someone moved divisions.

Any time you have a bunch of people working on collaborative projects, it can become very difficult to sort out who first came up with what. Add to that the fact that said people were working in different and operationally separate divisions of a very large company, not all of which communicated with one another, and it’s even tougher to create any kind of timeline. (It’s that much harder if you’re partially reliant on secondary sources that don’t grasp the separation of GM divisions in this era.)

Having been delving through his work in recent months, I don’t think Oliver Kelley was involved with the UPP concept to any great extent. Until he became Buick chief engineer, he was principally involved with transmission development; he did some concepts for rear transmissions or transaxles, but I’ve been digging through dozens of his patent filings and haven’t seen anything pertaining to FWD.

(P.S. Comments here are screened — it’s the only way I can keep a handle on all the spam — so if you post a comment and it doesn’t immediately appear, it just means I’m not online to approve it immediately.)

Thank you for your response. I thought that there was a problem with my comments. For Charles Chayne, I’m more certain because I have read an Bill Mitchell’s interview where he told that he (Chayne) saw the FWD car as a sedan or wagon rather than as Harley Earl which envisionned a fwd as a sport car. In your article, you tell that the early F-85 prototype was featured by a four speed hydramatic however the GMEJ articles learnt us the use of a two speed dual path transmission on a running prototype and a four hydramatic in a testing fixture.

As I said before, I haven’t read the Engineering Journal material, so it’s difficult for me to comment usefully on what it does or doesn’t say. The account in this article is based on the recollections of some of the Oldsmobile development engineers as quoted in other sources. They indicated that the test mule’s transmission was based on Hydra-Matic. Since those accounts were years after the GMEJ feature, it’s possible they were misremembering it or that the two accounts are talking about different things.

That said, it would make a certain amount of sense to use the Dual-Path transmission in such test mules simply because it was substantially lighter and somewhat more compact than even the smaller version of the three-speed Hydra-Matic and weighed less than half as much as the four-speed Hydra-Matics.

Fair enough.

Two points I was trying to make were: Both corporate Central Engineering and Oldsmobile had separate FWD UPP development plans for a very long time; and Fisher Body had a huge role in the production engineering of the main body.

All that changed when GM reorganized and Fisher Body was changed to GM Assembly, while the divisions didn’t go off on tangents by themselves. A more coordinated approach was taken which baffled customers finding Chevy engines in Olds cars and so on.

I love that first Toronado, but now I feel that I shouldn’t have even mentioned the GMEJ to you. I was just surprised you didn’t have access to the Engineering Journal given the huge list of other references.

It would certainly be of interest, but how I would lay hands on such a thing is quite another question. Neither the county nor the city public library systems have it, and while it’s conceivable that my alma mater’s engineering libraries might, that would probably be a project in itself. (I assume they would theoretically let alumni browse the collections, although I don’t know that I could check anything out that way even if it were circulating — probably not.) If I ever get a chance to take a look at it, I certainly will and I’ll bear your thoughts in mind. I don’t dismiss them by any means, it’s just hard for me to comment without actually having access to the material.

I have a 1970 Toronado GT that I was thinking about putting in a Manual transmission with an overdrive. Will that be possible especially since the Toronado was more of a luxury car.

I’m not qualified to provide any kind of mechanical advice, particularly on an endeavor of the magnitude of what you’re describing. To add an overdrive manual transmission to a first-generation Toronado, you would basically have to MAKE a new transmission with reversed-rotation gears and a detached bell housing that would fit in the space intended for a TH425. Any off-the-shelf parts would probably have to be modified extensively and a lot of the cases and linkages would likely need to be fabricated from scratch. It would be a major engineering project, not a shade-tree swap. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone has done it, but I can’t imagine it was cheap or easy.

I have a 1966 Toronado with an early production number of 19,014. Is it true that some of the early Toronados came with a Pontiac green painted emgine?

Does anyone know if the early production ’66 Toronados came with the engines painted with the Pontiac green paint or were all of them painted the slate blue?

Thanks,

Paul

66 and 67 were not painted slate blue. That color started with the 455

Just purchased my dream car back after 40+ years. Unfourtnately, Uncle Sam did not issue her in my seabag and my father could no longer store her. Soon, I will be working on my 66′ Toronado and would appreciate anyone that has a conversion for disc breaks. I am a bit worried of the safety factors and not so much mine. Any help and knowledge would be appreicated.

Thanks,

Michael

I’m not qualified to advise you on modifying your car, I’m afraid. As you may know, front discs became optional on the Toronado for 1967, but I don’t know if those can be added to a ’66. (I don’t think it’s a straightforward swap and would likely require replacing more than just the brakes.)