The 1969 Opel GT was Opel’s first show car and the German company’s first two-seat sports car since before World War II. Based on the humble Kadett B and often considered a miniature Corvette, the GT also owed a great deal to Chevrolet’s compact Corvair and a concept car once intended to replace the ‘Vette. In this installment of Ate Up With Motor, we take a look at the origins, history, and fate of the 1969–1973 Opel GT and its various planned successors.

CORVAIR ROOTS: THE MONZA GT

Although the Chevrolet Corvair, launched in October 1959, was not the U.S.-market sensation GM hoped, it made a strong impression on European automakers. The Corvair was not exported in large numbers, but its styling was extremely influential, spawning imitators ranging from Volkswagen’s Type 34 Karmann Ghia to the Hillman/Sunbeam Imp. Some European stylists also essayed custom-bodied Corvairs of their own, like the 1961 Pininfarina Speciale and the 1963 Bertone Testudo, a fastback coupe with a lift-up canopy in place of conventional doors.

Not to be outdone, the Chevrolet studios turned out a few radical Corvairs of their own, most with shortened wheelbases and very sporty styling. The earliest of these, the Sebring Spyder and Super Spyder, were primarily showpieces, intended to tease new production models. In 1962, however, work began on a somewhat more serious project, known internally as XP-797. There were two variations: a rear-engined roadster, later dubbed Monza SS, and a mid-engine coupe, the Monza GT.

While some accounts assert that the Corvair Monza GT was inspired by the Bertone Testudo, we believe the GT was actually designed and built before the Bertone car, which as best we can determine was not completed until later in 1962. We don’t have dimensions for the Testudo, but the Monza GT is considerably smaller than a stock Corvair: 165 inches (4,191 mm) long and 62 inches (1,575 mm) wide on a 92-inch (2,337mm) wheelbase. Inside, the seats are fixed, with adjustable pedals and a telescoping steering wheel. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

The Monza GT coupe was designed by Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine and engineered by Chevrolet’s Research & Development department. Developed over the course of about 10 weeks in the spring of 1962, the GT was a racy-looking fastback with a three-piece fiberglass body on a semi-unitized aluminum platform. Like the Bertone Testudo, it had a one-piece canopy that flipped forward for entry and exit; the front and rear body sections also tilted up for access to the powertrain and suspension. While the engine was a stock dual-carburetor Corvair flat six, it was mounted ahead of the rear axle, making the GT a mid-engine car.

Both XP-797 cars had fully independent suspension with double wishbones and torsion bar springs both front and rear, four-wheel disc brakes, and magnesium wheels. The doors above and below the GT’s nose flip open clam-shell style to expose rectangular Cibié halogen lights. What looks like a blister in the center of the hood is actually the fuel filler; there are two fuel tanks, both mounted in the front fenders. (Photo © 2003 Patrick McLaughlin; used with permission)

The GT and SS roadster were first seen in public at the Sports Car Club of America’s Elkhart Lake 500 in June 1962, followed by appearances at a number of other SCCA events. Those excursions were apparently for development purposes rather than publicity; in fact, Chevrolet asked journalists not to talk about the experimental cars until around the time of the car’s formal debut at the New York Auto Show in April 1963.

Bill Mitchell, then vice president of GM Styling, wanted to see the Monza GT in production — in fact, he later claimed that he saw it as a potential successor to the recently introduced Corvette Sting Ray. However, that idea found little management support. The Corvette itself was still on shaky ground as far as the corporation was concerned and Mitchell said Chevrolet was just not interested. The XP-797 project was abandoned, although the Monza GT and SS survive today in the collection of GM’s Heritage Center.

Although it originally had a stock dual-carb 2,372 cc (145 cu. in.) Corvair Monza engine, the Monza GT eventually received a heavily massaged version of the turbocharged Monza Spyder engine, expanded to around 3 liters (183 cu. in.) and making about 200 hp (149 kW). The rear window louvers can be closed completely to improve aerodynamics at the cost of rear visibility. Note the cropped Kamm tail and its quad taillights, features that would later reappear at Opel. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

STYLING AT OPEL

The stylistic impact of the Corvair was not lost on officials of GM’s German subsidiary in Rüsselsheim. Adam Opel AG was then doing respectably well in Europe, building around 300,000 cars a year, but stylistically, it simply didn’t rate. Opel didn’t even offer convertibles or hardtops in those days, just an array of competent but dull sedans and Kombis (wagons).

Unlike its U.S. parent, Opel didn’t indulge in fanciful show cars, either. Rüsselsheim’s tiny design staff comprised fewer than a dozen artists and modelers crammed into a rather small space, reporting to chief engineer Hans Mersheimer. Any advanced concepts they may have developed were strictly for internal consumption.

A first-year Corvair coupe (top) and one of its many European scions, in this case the Sunbeam version of the Rootes Group’s rear-engined Imp (bottom). This is a 1970 Imp, but the first iteration, launched in 1963, looked much the same. The Corvair resemblance is hard to miss. (author photos)

By 1961, Nelson J. Stork, then Opel’s managing director, and E.S. Hoglund, GM’s VP of overseas operations, had decided that Rüsselsheim needed an infusion of U.S. design talent. Bill Mitchell arranged for Hoglund to interview some of his top designers, including Chuck Jordan, then chief stylist for Cadillac, and Irv Rybicki, then head of the Oldsmobile studio. The one Opel management ultimately selected, however, was Clare MacKichan, for the last decade the chief stylist of Chevrolet. MacKichan had overseen a variety of memorable designs, including the Corvette, the 1955–1957 Chevrolets, the Nomad, and of course the Corvair. In early 1962, MacKichan was transferred to Rüsselsheim, with Irv Rybicki taking his place at Chevrolet.

Under MacKichan’s direction, Opel’s styling department gained additional staff and a new design center. Unsurprisingly, over the next few years, Opel’s production cars began to take on a more American look. If they had been fitted with sealed-beam headlights, cars like the bigger Rekord B and C wouldn’t have looked out of place in contemporary Chevrolet catalogs. Indeed, the new Kadett was sold through some U.S. Buick dealers.

Although many Opel Kadetts of this vintage (particularly in Germany) had the older 1,078 cc (66 cu. in.) pushrod engine, some later examples received the the newer cam-in-head (CIH) engines from the bigger Opel Rekord. U.S.-bound Kadetts could be ordered with the 1,491 cc (91 cu. in.) or 1,897 cc (116 cu. in.) CIH engines, but not this German sedan’s 1,698 cc (104 cu. in.) version. (Photo: “Kadett 1700 Front” © 2007 Christoph Zehnder at German Wikipedia; released into the public domain by the photographer, resized 2013 by Aaron Severson)

THE OPEL EXPERIMENTAL GT

Another of MacKichan’s moves was to establish a new Advanced Design group, headed by Erhard Schnell, a designer who had been with Opel since the early 1950s. Among the Advanced group’s early projects was a sports car, something Opel hadn’t even contemplated in some 40 years. Known internally as Projekt 1484, the sports car was initially developed in great secrecy. Even Nelson Stork didn’t see it until 1963, many months after the project began.

As it took shape, Projekt 1484 began to look quite a bit like the Monza GT. The Opel design was not mid-engined, nor was it in any way Corvair-based, but it shared many design cues with the Monza: a sloping nose with concealed headlamps, a low-slung fastback roofline, and a cropped Kamm tail with quad taillights.

We don’t know if MacKichan had been involved with the development of the XP-797 (it appears that the Monza SS and Monza GT were built after he left for Germany), but Bill Mitchell later confirmed that the Opel design was indeed based on the Monza GT, a design of which Mitchell was very fond. An additional connection was Tony Lapine, who joined MacKichan at Opel in 1964 and was involved in the sports car project’s subsequent development. (Interestingly, while Projekt 1484 did not share the Monza GT’s lift-up canopy, that feature reappeared on the 1969 Opel CD, a concept car based on the Diplomat 5,4.)

By 1965, Projekt 1484 had reached the full-size prototype stage. While it had found some support outside the styling department, principally from marketing executive Bob Lutz, senior Opel officials had little interest in pursuing the project even as an auto show confection. Opel’s philosophy at the time was that the company should show what it sold, and Opel was not in the sports car business.

In July 1965, Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen was promoted to group VP of GM’s Overseas and Canadian Group, following successful stints as general manager for Pontiac and Chevrolet. MacKichan had worked with Knudsen at Chevrolet and knew of his fondness for sporty cars. We assume that most GM executives were aware that Knudsen had revived the moribund Pontiac division with a new emphasis on performance. Suspecting that the sports car would be right up Knudsen’s alley, MacKichan and Lutz arranged for him to see the prototype. As expected, Knudsen loved it and gave his support for exhibiting the car on the auto show circuit.

One of the early prototypes of Projekt 1484, the Opel Experimental GT. Note the comparatively featureless nose, lacking the production car’s under-bumper grille and cooling ‘nostrils.’ There is no hood bulge, either; the experimental four-throat Solex carburetor set-up didn’t require it. Another major distinction is the prototype’s electrically operated rectangular pop-up headlights, chosen to minimize aerodynamic interference in the raised position. In back, the prototype sports a Kamm tail with quad taillights reminiscent of the Monza GT and SS, albeit with vestigial bumpers. The similarity to the Monza GT was not lost on contemporary automotive journalists. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

The prototype made its public debut at the Frankfurt International Auto Show in October. Prosaically dubbed Opel Experimental GT, it was described as an aerodynamic test chassis for Opel’s new high-speed test track in Dudenhofen. Despite that cautious presentation, response was sensational. The car attracted hordes of curious showgoers and raised many eyebrows among the representatives of other automakers, who expected nothing more from Opel than bland porridge.

Seeing the enthusiastic reaction, Opel management reexamined the sports car project in a new light. There seemed to be a market for a production model. The question now was how to build it.

THE GT AND THE KADETT

Given the sports car’s likely volume — and the likely complexity of its body — Opel decided to outsource production of its body shell. Initial thoughts involved Karmann, but in early 1966, Opel officials met with representatives of the venerable French coachbuilder Brissonneau & Lotz, who had been trying unsuccessfully to pitch the idea of a Rekord convertible.

Brissonneau & Lotz were interested and signed a deal to produce tooling and bodywork for the prototypes. The actual stamping, welding, and body assembly would be subcontracted to the Parisian firm Chausson, best known today for its recreational vehicles. The Brissonneau & Lotz plant in northern France would handle paint, trim, and wiring before sending cars back to Opel’s Bochum plant for mechanical assembly.

The Opel GT’s brother under the skin, the Kadett B, seen here in LS fastback coupe form. It was built at Opel’s plant in Bochum-Laer, which opened in late 1962 specifically to build the Kadett. The GT shared the Kadett’s floorpan, although the GT’s front suspension was relocated forward slightly, increasing its wheelbase from 95.1 to 95.7 inches (2,415 to 2,428 mm), and its tread widths were 0.4 inches (10 mm) wider. (Photo: “Opel Kadett B Coupé LS (2008-06-28)” © 2008 Spurzem – Lothar Spurzem; resized 2012 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Germany license)

There was little chance of any exotic hardware under the skin. Even if Opel management had been willing to make large investments in a relatively low-volume new product, selling price was a concern. Market research suggested that the sweet spot would be around 10,000 DM (about $2,500 at the contemporary exchange rate), where the new car would face little direct competition. At that price, a bespoke platform was out of the question. Instead, the sports car would share most of its mechanicals with the Kadett B.

The one major concession the stylists and engineers wanted was the location of the engine. The Kadett’s engine was normally mounted well forward in the interests of packaging efficiency, which was problematic with the sports car’s sloping nose. To preserve the prototype’s sleek profile, the styling team wanted to relocate the engine 15.75 inches (40 cm) farther back, but Opel’s cost accountants balked, seeing the engine relocation as an unnecessary expense.

Hoping to appeal to Teutonic pride of engineering, proponents insisted that the change would make a perceptible difference in the car’s handling and overall feel. To test that thesis, Hans Mersheimer authorized the construction of two test mules, one with the engine relocated, one without, and hired Porsche works driver Hans Hermann to test both at the Nürburgring. Predictably, Hermann’s professional opinion was that the car with the relocated engine felt better, so Opel management grudgingly conceded the point.

Like the Kadett A, the Kadett B’s front suspension used upper and lower control arms with transverse leaf springs and a torque tube rear axle. Early cars had parallel leaf springs in back, later exchanged for coil springs with radius rods and a Panhard rod for axle location. That layout was previewed on the original Opel Experimental GT and introduced to the Kadett line by 1968. (Photo: “Opel Kadett B Coupé LS – Heck (2008-06-28)” © 2008 Spurzem – Lothar Spurzem; resized 2012 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Germany license)

The running prototype shown to the press in 1967 had the 1,897 cc (116 cu. in.) version of Opel’s new cam-in-head (CIH) engine, recently introduced on the Rekord. In the prototype, the engine used an experimental 4V Solex carburetor and a modified head with 10.0 compression, giving a net output of 128 PS DIN (126 hp, 94 kW) and 115 lb-ft (156 N-m) of torque. Since the prototype weighed less than a ton and was quite slippery aerodynamically, it had excellent performance and a claimed top speed of 130 mph (210 km/h). It looked very promising.

THE PRODUCTION OPEL GT

Clare MacKichan departed long before Opel’s new sports car went into production. In 1967, he returned to the U.S. to become director of advanced styling, turning over the reins at Opel to Chuck Jordan, who had spent the previous five years as GM’s director of exterior design. Jordan would oversee final development of the production sports car, now known simply as Opel GT.

Inevitably, the GT’s shape underwent many changes between prototype and finished product, emerging taller, thicker of snout and plumper of hindquarters, with a more sharply cropped tail, a prominent hood bulge, and a pair of cooling slits atop the nose. Some of the changes were undoubtedly driven by production necessity, others by regulatory requirements (the prototype’s rectangular pop-up headlights would not have been legal in the U.S.), while others were dictated by wind tunnel testing. In production trim, the GT had a drag coefficient of 0.39: not great by today’s standards, but first rank for the late 1960s and significantly better than the C3 Corvette, to which the Opel was now taking on a decided and probably non-coincidental resemblance.

The production Opel GT was 2.75 inches (70 mm) taller than the prototype, but it still stands a mere 48.2 inches (1,224 mm) overall. The GT was not otherwise a tiny car; at 161.9 inches (4,112 mm) long and 62.2 inches (1,580 mm) wide overall, it was longer and wider than a Triumph TR6. Curb weight was about 1,910 lb (866 kg) for the 1100SR, 2,120 lb (962 kg) with the 1.9-liter engine. (Surprisingly, even with the relocated engine, weight distribution was an unspectacular 54/46% front/rear.) Note the flush glass, roof-cut doors, and lack of rain gutters, all aerodynamic measures. (author photo)

Like the prototype, the production Opel GT’s chassis was borrowed almost whole cloth from the Kadett. Steering was rack-and-pinion, with a faster ratio than the sedan’s, while solid-rotor front disc brakes and a four-speed manual gearbox were standard. Opel’s new three-speed Strasbourg (TH180) automatic was optional. Front suspension was by upper and lower control arms with a transverse leaf spring while the rear used variable-rate coil springs and a torque tube axle located by twin radius arms and a Panhard rod. A rear anti-roll bar was optional, as were a heavy-duty suspension package and limited-slip differential.

The GT’s base engine would be the 1,078 cc (66 cu. in.) OHV four from the Kadett Rallye, with two single-throat carburetors and 67 gross horsepower (50 kW; 60 PS/44 kW net). The 1,897 cc (116 cu. in.) cam-in-head engine would be optional, although it would be the mildly tuned 1900S version available on the Kadett and Rekord, with a single two-throat Solex and 102 gross horsepower (76 kW; 90 PS/66 kW net). We assume the prototype’s 128 PS engine was deemed either unsuitable or too expensive for production.

Even with the relocated engine and a modified valve cover, the air cleaner snorkel of the 1900 S engine would not clear the Opel GT’s sloping hood, so a blister was added for clearance. The same issue also kept Opel from installing the hotter 1900 H engine from the Rekord Sprint, which made 106 PS (105 hp/78 kW) with two Weber carburetors; the latter wouldn’t fit under the GT’s hood. Tuners who installed multiple carburetors on the GT often resorted to either modifying the engine bay for clearance or foregoing air cleaners, obviously problematic for non-racing use. (author photo)

FACING THE MARKETPLACE

The start of Opel GT production was delayed by the general strike that shut down most of French industry in May 1968, but the first few hundred preproduction cars were completed that summer with regular production commencing in September.

To make up for the delays, Opel opted to have about half of first-year GT production trimmed in Bochum rather than in France. A preproduction GT appeared at the Circuit de la Sarthe shortly before the start of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1968, driven by Olympic skiing star Jean-Claude Killy, recently hired as a GM spokesman. The production car went on sale in Europe that October.

In Germany, the basic Opel GT-A 1100SR started at 10,767 DM (equivalent to about $2,750), above the original target, but not disastrously so. The GT-AL 1900S started at 11,877 DM (a little over $3,000). The federalized GT, which arrived in the U.S. in the spring of 1969, was offered in a single well-equipped trim level with a base price of $3,395; the 1.9-liter engine was a $99 option. Compared to a Porsche 912, that was a bargain, but the GT was more expensive than likely rivals such as the Fiat 124 Coupé, the Triumph TR6, or the new Ford Capri. A German Capri 1700GT, for example, undercut the GT-A 1100SR by almost 2,800 DM (more than $700).

European Opel GTs came with halogen driving lights, which were omitted on North American cars to avoid problems with U.S. lighting regulations. The slots above the bumper admit air to the radiator, although the primary intake is on the underside of the nose, behind the grille. (author photo)

The automotive press didn’t exactly receive the Opel GT with open arms. While the Opel was named 1969’s best-styled production car by Italy’s Style Auto magazine, other critics found the production GT less appealing than the cleaner, less gimmicky prototype. There was also a general turning up of noses about the GT’s Kadett origins, although reviewers acknowledged that very few affordable sports cars of the time didn’t share their underpinnings with workaday sedans.

For all the carping, reviewers admitted that the GT certainly looked the part both inside and out. The swoopy exterior was matched with a well-trimmed cabin with full instrumentation, fine seats, and above-average ergonomics. The GT also rode surprisingly well. If you could live with its limited luggage space, mediocre ventilation, and noisy engine, it scored well as a touring car.

As a sports car, however, the GT sent mixed messages. The manual shift linkage was slick and precise, the steering quick and accurate, but most enthusiast reviewers complained that the GT’s handling was more Buick than Bavarian. The principal culprit was the lackluster grip of the Opel’s skinny tires, but their cause was not helped by the standard suspension, whose lack of roll control contributed to substantial body lean and heavy understeer. The GT also tended to unload and spin its inside rear wheel in tight turns. European buyers could address the latter problem with a limited-slip differential and mitigate the former with heavy-duty suspension and/or a rear anti-roll bar, but curiously none of those items was offered on U.S. cars, although the suspension pieces were similar or identical those of the Kadett Rallye.

In addition to its large tachometer, the Opel GT’s dashboard included both gauges and warning lights for amps, oil pressure, and water temperature (although the secondary gauges were deleted on the GT/J to reduce costs). Reviewers liked the four-speed gearbox’s shift linkage (despite a gap in ratios between second and third that was frustrating in U.S. driving conditions), but were split on the pedal location. Some appreciated that the throttle and brake were close enough to facilitate heel-and-toe downshifts; others thought the pedals were too close together. Many critics were also annoyed by the lack of face-level vents. (Photo © 2009 Robert Nichols; used with permission)

The GT did have decent straight-line performance, at least with the 1.9-liter engine. Since the GT weighed about 200 lb (91 kg) more than a Kadett, the 1100SR engine provided rather sleepy acceleration; 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) took more than 16 seconds, although top speed was a respectable 96 mph (155 km/h). The 1900S engine allowed the GT to reach 60 mph (97 km/h) in around 10 seconds, hot stuff by contemporary European standards. Given enough room, the 1900S would pull to 6,000 rpm in top gear, giving a top speed of 115 mph (185 km/h).

For the average buyer, the Opel GT felt nimble and sporty, and it offered show car looks, good performance, and excellent fuel economy (up to 28 mpg (8.4 L/100 km) on the highway) for a reasonable price. Model year production totaled more than 30,000 units, 11,880 of which were sold in the U.S.

One of the less happy similarities between the Opel GT and contemporary Corvettes was the lack of any exterior luggage access. A few small suitcases could be loaded through the doors into the carpeted area behind the seats, but there was neither a trunk nor any pretense of 2+2 seating. The spare tire and jack were concealed by a detachable vinyl cover. This car’s wheels and tires are not stock; 1.1-liter GTs came with 155SR13 tires, 1.9-liter cars with 165HR13s, all on steel wheels. (author photo)

OPEL GT VS. 240Z

The Opel GT returned for 1970 with a variety of minor refinements. The most notable was that factory air conditioning was now optional, reinforcing the perception that the GT was more of a stylish tourer than a sports car. The 1100SR engine remained nominally standard, but it was on its way out, having sold poorly even in Europe. It accounted for only about 10% of 1969 production and a tiny handful in 1970. The grand total was only 3,573 cars.

With the 1900S engine, the Opel GT acquitted itself well against rivals like the aging MGB, but the Opel had a formidable new rival in the Datsun 240Z, which arrived in the U.S. for the 1970 model year. The Z was slightly bigger than the Opel, just as well equipped, and far more powerful, with 151 hp (113 kW) from its 2,393 cc (146 cu. in.) six. It also had better handling than the GT, with fully independent suspension. In Europe, import duties tended to push the Datsun into a higher price class, but U.S. cars were aggressively priced, listing for only about $100 more than a GT with the 1.9-liter engine. Against the Z, the Opel’s only real tangible advantage was that it was possible to get one for something close to list price, while Datsun buyers faced waiting lists and substantial dealer markup.

At the 1969 Frankfurt show, Opel showed a lift-roof version of the GT, the Aero GT. Developed by styling director Chuck Jordan, it bears a remarkable resemblance to the later Pininfarina-styled Dino 246 GTS. Two of these cars were built, but for whatever reason, Opel decided not to pursue the lift-roof version for production. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

GT production was down for 1970, but still topped 24,000 units, not bad for a small two-seater. European sales slumped badly, however, thanks, we suspect, to the popularity of the less pretty but more practical Capri. More than 85% of GT production now went to the U.S. Hoping for a little extra publicity, Buick became a sponsor of the popular TV spy spoof Get Smart. The fictional Maxwell Smart drove a Rallye Gold Opel GT throughout the show’s final season, which coincided with the 1970 model year.

TUNING POTENTIAL

Despite stock Opel GT’s middling performance, it had obvious potential. In 1970, Opel dealers in Italy persuaded Turin-based race builder Virgilio Conrero, famous for his Alfa Romeo racers, to prepare the GT for Group 4 competition.

The Conrero cars had five-speed ZF gearboxes, flared fenders, wider wheels, and an upgraded suspension with anti-roll bars and a Watt’s linkage replacing the Panhard rod. Their engines were bored out to 1,979 cc (121 cu. in.) and tuned for about 185 hp (138 kW). Conrero GTs competed in a variety of events from 1971 to 1973, including the Sestriere hill climb and the Monza, but their best showing was the 1971 Targa Florio, where a Conrero Squadra Corse GT driven by Salvatore Calascibetta and Paolo Monti won the under-2-liter GT class, taking ninth place overall. A few Conrero GTs were sold to private customers and Conrero offered tuning kits for interested buyers.

Around the same time Conrero started work on his GT, Henri Greder of the Greder Racing Team obtained two cars of his own through designer Franco Sbarro. The Greder cars were also expanded to about 2.0 liters (122 cu. in.) and fitted with cross-flow heads, giving around 200 hp (149 kW). When Sbarro and Greder were done with them, the cars themselves were Opel GTs in name only, with new tubular-steel chassis, fiberglass body panels, and fixed headlamps. One Greder GT, driven by Jean Ragnotti, achieved 10th place in the Lyon-Charbonnières Rally, but the cross-flow head proved problematic. Greder soon abandoned the GT in favor of newer Opels.

Opel’s long-serving CIH engine, seen here in a European Opel GT-AL 1900, with a single two-throat Solex 32 DIDTA-4 carburetor and a modified valve cover to clear the GT’s low, sloping hood. The CIH (“cam in head”) engine had a single chain-driven camshaft mounted in the cylinder head adjacent to the valves, actuating them via stamped steel rocker arms. For its day, the CIH engine offered excellent mid-range torque and respectable specific output, but its noise levels and refinement were much criticized; Car and Driver compared it to a tractor engine. (Photo © 2011 RUD66; used with permission)

Another source of customized GTs was former BMW team manager Klaus Steinmetz, who offered an assortment of factory-approved tuning kits for Opel engines. Steinmetz offered a series kits for the 1,897 cc (116 cu. in.) CIH engine, ranging in output from 107 to 140 PS (79 to 103 kW), as well as a full-race version with around 200 PS (147 kW). The kits were sold in the U.K. through John Rhodes Tuning in Birmingham, but emissions restrictions meant that they weren’t available in the U.S.

Opel also used the GT as the basis for a number of one-offs, the most famous of which was the Diesel Rekordwagen, with special aerodynamic bodywork and a 2,068 cc (126 cu. in.) turbodiesel engine. In July 1972, the Rekordwagen averaged 119.3 mph (190.9 km/h) for 72 hours on Opel’s test track in Dudenhofen, setting a host of speed and endurance records.

The Opel GT received very few styling changes over the course of its short life, but you can distinguish the 1969-1970 cars from the 1971–1973 models by the location of the “Opel GT” badges. Early cars carry their identification on the front fenders, aft of the front wheelhouses, while on later models, the ID badge is on the tail, just below the fuel filler. This 1971 GT’s white side marker lights probably came from a European model; U.S. cars had amber lights. (author photo)

In the U.S., the best-known tuned Opel GT was probably the one modified by Car and Driver magazine in 1970. Christened “J. Edgar Opel,” the C/D car had a blueprinted but emissions-legal engine with freer-flowing exhaust headers, making 100 net horsepower (75 kW), about 11 hp (8 kW) more than stock. The magazine also fitted a limited-slip differential with a 4.22 axle ratio (not on the U.S. options list, but homologated for competition), front and rear anti-roll bars, and a set of E60-15 Goodyear Wide Oval tires on Minilite wheels (the installation of which involved reshaping the inner fenders). The modifications trimmed more than a second from the GT’s 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) times and improved cornering and braking grip considerably, but the big tires, extra unsprung weight, and aftermarket anti-roll bars created clearance problems, compromised ride quality and revealed the basic limitations of the front suspension geometry. The C/D car was eventually sold to artist Russ von Sauers, Jr. We don’t know if it still survives.

THE OPEL GT/J

While Opel made no move to offer any performance upgrades as factory options on the GT, the production car could have used the help. For the 1971 model year, GM mandated that all its U.S. engines be detuned to allow the use of lower octane low-lead and unleaded gasoline. Since the 1900S engine was octane sensitive (testers noted that it could ping even on 98 RON fuel), Opel reduced the compression ratio of federalized versions to only 7.6:1. Power nosedived, dropping from 102 to 90 gross horsepower (76 to 67 kW); SAE net output was now a meager 78 hp (58 kW). The lower compression ratio was accompanied by a switch from mechanical to hydraulic lifters, which were quieter, but cut the CIH engine’s usable rev range by about 600 rpm. The changes increased the GT’s 0-60 mph (0-97 km/h) times by more than a second and reduced top speed by about 5 mph (8 km/h).

The small slots above the Opel GT’s backlight are exhaust vents for cabin air. As with the C3 Corvette, many critics found the GT’s flow-through ventilation system inadequate in warm weather, particularly on cars without air conditioning. This car’s rear window louvers are not stock, but they do underscore the resemblance between this car and the earlier Monza GT concept car. (author photo)

The GT also faced another difficult new rival, this one from Opel itself. The new Manta coupe, Rüsselsheim’s answer to the Ford Capri, arrived for the 1971 model year, offering sporty styling (including a GT-like Kamm tail), similar performance, and much greater practicality for a significantly lower price. Despite its larger dimensions, the Manta wasn’t substantially heavier than the GT and actually handled better, thanks in large part to a new coil spring front suspension and anti-roll bars at both ends. Even in Europe, where the GT’s straight-line performance remained unchanged, it was hard not to see the Manta as a better value.

A 1972 Opel Manta coupe, seen here in 1600S form with a 1,584 cc (97 cu. in.) CIH engine making 80 PS DIN (59 kW). Introduced in the fall of 1970, the Manta was based on the new Ascona sedan, although the coupe actually bowed first. In the U.S., both the Ascona and Manta were initially sold as the Opel 1900, although federalized coupes belatedly adopted the Manta name for 1973. Buick decided to import only the 1,897 cc (116 cu. in.) CIH engine, probably to simplify emissions certification. (Photo: “Opel Manta A first registered in England November 1971 1600ish cc” © 2011 Charles01; resized 2012 by Aaron Severson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license)

Opel GT production for 1971 dipped below 15,000 units, fewer than 1,100 of which were sold in Europe. To make matters worse, in 1970, Renault had purchased controlling interests in both Brissonneau & Lotz and Chausson. Since Renault considered the GT a competitor for its own Alpine A110, Opel was compelled to move production entirely in-house, an unwelcome extra expense for a low-volume model.

Hoping to boost sales by appealing to younger buyers, Opel introduced a new GT model at the 1971 Geneva auto show. Called the GT/J, it was comparable to American budget Supercars like the original Plymouth Road Runner: a brightly painted 1.9-liter Opel GT stripped of all nonessentials, including chrome trim and carpeting. Starting at 10,685 DM (about $3,070), the GT/J was still slightly more expensive than a Capri 2300GT, but considerably more affordable than the plusher GT-AL 1900S. The GT/J was not sold in the U.S., but it was moderately successful in Europe, accounting for 10,760 units through 1973.

RUN OUT

The introduction of the GT/J brought total Opel GT production to more than 17,000 units for 1972, but the end was in sight. The Kadett was about to be redesigned, so continuing the GT past 1973 would have necessitated a major revamp to accommodate the floorpan of the new Kadett C and the 5 mph (8 km/h) bumpers that would be required for U.S. cars starting in 1974. Furthermore, the rising value of the Deutschmark following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates would make it difficult to hold the line on price, something that would ultimately drive Opel out of the American market entirely.

Perhaps the Opel GT’s most distinctive feature is its retractable headlights. When the lights are engaged via a dashboard lever (mounted just ahead of the gearshift), both light covers rotate sideways, toward the left side of the car, to expose the headlamps on their undersides. When each headlamp locks into its upright position — usually accompanied by an audible clunk — a switch automatically activates the light, at least as long as the contacts are not worn or damaged. If the headlamp units are not fully engaged, a white warning lamp is illuminated on the dashboard. (Photo © 2011 RUD66 (Rudi Simon); used with permission)

The GT returned for the 1973 model year, but it would be for the last time. A sure sign of the model’s imminent demise was that when Opel prematurely ran out of taillights in early 1973, they hastily adapted the lights from the Manta rather than ordering more of the original units. European cars were little changed otherwise, but federalized GTs had further emissions-related changes, reducing output to 75 net horsepower (56 kW) and 92 lb-ft (125 N-m) of torque.

Opel GT production ended in August, although some leftover cars lingered on dealer lots into 1974. The final tally was 103,464 units.

GT/W, GT/2, AND THE BLACK WIDOW

In the early 1970s, Opel considered a number of possible successors for the GT, including one based — once again — on a mid-engined car intended to replace the Corvette.

In 1971, Clare MacKichan’s Advanced studio in Detroit developed the XP-897GT, a mid-engine car based around GM’s two-rotor GMRCE2 Wankel engine, then in development. The XP-897GT, built but not designed by Pininfarina, debuted at the Frankfurt International Auto Show in October 1973 as the Corvette 2-Rotor. Had it reached production, GM considered offering an Opel version as a next-generation GT. Opel stylists developed their own mid-engine rotary concept, originally called GT/W (for Wankel), but the termination of GM’s rotary engine project meant that the GT/W got no further than the non-running prototype stage. It was shown publicly in 1975 as the Opel Genève.

We don’t know how directly the Opel GT-W was based on the XP-987GT/2-Rotor, but except for the Opel’s concealed headlamps, the two designs look very similar, particularly in the relationship between the side windows and the rear quarterlights. Unlike the 2-Rotor, the GT-W/Genève was only a mockup, not a drivable prototype. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

An alternative was another in-house Opel concept, a fastback 2+2 coupe nicknamed “Schwarze Witwe” (Black Widow), a name previously applied to Tony Lapine’s own modified Kadett (which allegedly inspired the original Kadett Rallye). Presumably based on the Kadett C, the Schwarze Witwe was seriously considered for production, but was canceled during the OPEC oil embargo in 1973–1974.

The Schwarze Witwe looked very different from the Opel GT, with a rounded fastback roofline, forward-swept, glassed-in B-pillars, and 2+2 seating. This prototype’s covered headlights would not have been legal in the U.S. and there don’t appear to be any provisions for meeting U.S. 5 mph (8 km/h) impact standards. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

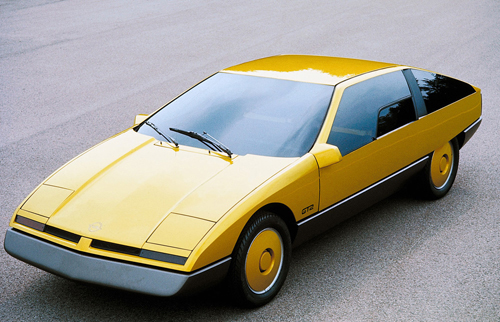

In 1975, some months after the public unveiling of the Genève, Opel developed a sleek, futuristic concept car called the GT/2, which was shown at Frankfurt, London, and Paris late that year. Built by Michelotti but developed by Erhard Schnell’s Advanced studio in Rüsselsheim (then under the direction of Henry Haga), the GT/2 was based on the GT/E version of the new Manta B, powered by a fuel-injected 1,897 cc (116 cu. in.) CIH engine. The GT/2 was even more aerodynamic than the first GT, with a claimed drag coefficient of only 0.33. It featured a hatchback roof and manually operated sliding doors with their latches concealed beneath the side mirrors. (Regular readers will recall that the latter feature was originally patented by Howard “Dutch” Darrin in 1948 and used on the short-lived Kaiser Darrin, although Darrin’s patent expired well before the GT/2 was built.) Opel officials suggested that a toned-down version of the GT/2 might become a production car later in the decade, but it never happened.

With its flush glass and sliding doors, the Opel GT/2 still looks futuristic today. To increase structural rigidity, the door glass is actually fixed, but there’s a small retractable window on each side to manage tollbooths and the like. As with the original GT, the engine is set back about 16 inches (406 mm) to clear the sloping hood. Inside, the cabin featured 2+2 seating and a digital instrumental panel. (Photo copyright 2012 General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.)

A second-generation Opel GT did not emerge until the 2006 Geneva auto show, going on sale later that year. Based on a 2003 Vauxhall concept car, the VX Lightning, the new GT was a two-seat roadster based on GM’s Kappa platform, shared with the Pontiac Solstice and Saturn Sky. Ironically, the new GT was built in the U.S. alongside its Pontiac and Saturn siblings, but it was sold only in Europe. The Kappa GT survived only three years, dying with the Solstice and Sky in the summer of 2009. Production totaled 7,519 units.

A Kappa-platform Opel GT roadster next to a vintage GT/J coupe. The modern Opel GT weighed over 1,000 lb (454 kg) more than its namesake, but it was substantially more powerful, making 260 hp (194 kW) from its 1,998 cc (122 cu. in.) turbocharged Ecotec four. Opel’s version of the Kappa platform did not offer the larger normally aspirated engine available in its Pontiac and Saturn brothers. (Photo © 2011 RUD66 (Rudi Simon); used with permission)

EPILOGUE

The original Opel GT has often been dismissed as a Kadett in a Corvette suit, but it wouldn’t have taken much to make the GT a credible sports car. Most of the pieces were there, and in some respects (aerodynamics, ergonomics, fit and finish) the GT was actually superior to the C3 Corvette. With more power and some chassis development work, the GT could have given sports cars like the Datsun 240Z a run for their money. Admittedly, getting more power out of the CIH engine while keeping it emissions-compliant for the U.S. market would have been tricky (fuel injection was only a partial answer — even with injection, the last U.S.-market Asconas and Mantas had only 81 net horsepower/60 kW) and exchange rates would have remained a sore point, but neither problem was necessarily insuperable.

We suspect the real challenge would have been convincing Opel management that making the low-volume GT into Europe’s answer to the Corvette was worth the investment. As the array of mooted successors indicates, Opel was not oblivious the GT’s value as a traffic builder, but, with the possible exception of the GT/W, Rüsselsheim’s thinking appears to have focused on greater practicality (e.g., 2+2 seating, greater cargo space) rather than greater performance. In some respects, that made sense; the GT sold well by Triumph or MG standards, but was nothing compared to the almost 2.7 million Kadetts Opel sold between 1965 and 1973. However, that also weakened the case for the GT as a separate product, particularly since Opel already had an attractive and perfectly competent four-seat sporty coupe in the form of the Manta.

The fate of the original GT suggests what might have happened to the Corvette had the ‘Vette not enjoyed continuing support from staunch defenders like Zora Arkus-Duntov and Bill Mitchell. The original Corvette was on very shaky ground for the first decade of its existence and at several points came close to either being canceled or transformed into a Camaro-like four-seater. While the Corvette eventually became one of GM’s most profitable cars, the GT didn’t last long enough to reach that point, perhaps in part because by the time its sales began to falter, many of the people who had originally championed it had moved on. Erhard Schnell was still running Opel’s Advanced Design studio, but both Clare MacKichan and Chuck Jordan had returned to the U.S., replaced by Dave Holls and later Hank Haga. Bunkie Knudsen had left GM in 1967, Bob Lutz had gone to BMW, and in 1969 Tony Lapine had gone to Porsche, where he would design the 928 and 924.

We think the original Opel GT was better off as a two-seater, but buyers probably would have appreciated it if Opel had relocated the fuel filler to allow a proper opening decklid.

The 1969–1973 Opel GT now has a fair collector following, although many cars have succumbed over the years to rust or collisions. The GT’s body was well assembled by the standards of its time, but it was not easy to repair and it was years before resale values were high enough to make full restorations worthwhile. Quite a few survivors have been modified as well, with everything from later CIH engines (which remained in use through the 1990s) to Weber carburetors and even small block Chevrolet V8s.

If the Opel GT never got the chance to become a great car, it was nonetheless an interesting one, and in some ways it was remarkable that it was built at all. The Monza GT never got past the prototype stage, nor did a contemporary sports car concept from Vauxhall, the 1966 VXR. The GT remains an attractive little car, but we can’t help thinking that it could have been much more than a pretty face.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Bob Nichols, Pat McLaughlin, and Rudi Simon (RUD66) for the use of their photos and Kathy Adelson and Larry Kinsel of the GM Media Archive for their kind assistance in locating historical images.

NOTES ON SOURCES

Information about the development and history of the Opel GT, including road test data, came from “1.9 Opel GT: Not bad but not up to expectations,” Road & Track Vol. 20, No. 10 (June 1969), reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, ed. R.M. Clarke (Cobham, England: Brooklands Books, Ltd., 2007), pp. 60-63; “1969-1973 Opel GT,” Sports Car Market, n.d., www.sportscarmarket. com, accessed 8 April 2012); “A Rare Opel,” World’s Fastest Sports Cars 1968, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 12-15; Sam Abuelsamid, “1969 Opel Aero GT is rarer than you think,” Autoblog 27 April 2010, www.autoblog. com, accessed 8 April 2012; the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, “Opel GT,” HowStuffWorks.com, 5 June 2007, auto.howstuffworks. com/ opel-gt.htm, accessed 8 April 2012; “Autotest: Opel GT 1900,” Autocar 11 September 1969, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 76-80; Patrick Bedard, “Car and Driver’s Opel GT,” Car and Driver Vol. 16, No. 1 (July 1970), pp. 29-33, 53; Jean Bernardet, “Opel GT in Production,” Style Auto No. 23 (April 1969); John Blunsden, “GM’s Second Sports Car,” Sports Car Graphic April 1969, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 26-29; Jim Brennan, “Hooniverse Lost Car Weekend – A 1972 Opel GT,” Hooniverse, 13 August 2011, hooniverse. com/ 2011/08/13/ hooniverse-lost-car-weekend-a-1972-opel-gt/, accessed 7 April 2012; Martin Buckley, “Drag Act,” Classic & Sports Car June 1993, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 38-42; “Car and Driver’s Opel GT,” Car and Driver Vol. 16, No. 2 (August 1970); reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 127-131; “Collectible Classic: 1968-1973 Opel GT,” Automobile October 2009, www.automobilemag. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Ican Coomber, “From Olympia to Monza – Opel in the United Kingdom,” Vauxhall Bedford Opel Association, 2006, www.vboa. org.uk, accessed 7 April 2012; Mike Covello, Standard Catalog of Imported Cars 1946-2002, Second Ed. (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2001); Eric Dahlquist, “The Conversation Factor,” Motor Trend Vol. 21, No. 8 (August 1969), pp. 36-38; “Der perfekte Keil: Alfa Romeo Junior Zagato, 1969 – 1975,” Zagato-Cars.com, n.d., www.zagato-cars. com, accessed 8 April 2012; “Die Opel GT Entwicklung,” Opel GT World, n.d., www.opelgtworld. de, accessed 8 April 2012; Ben Field, “Fruity Opel,” Practical Classics February 2002, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 150-153; Craig Fitzgerald, “1968-1974 Opel GT,” Hemmings Sports & Exotic Car #16 (December 2006), pp. 91-94, and “Opel Manta: GM’s Stylist Sport Sedan,” Hemmings Motor News March 2009; “GM’s [Germany] New GT,” Sports Car World November 1968, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 18-19; Charles Goin, “The Definitive Opel GT Guide for Year, Color and Parts Identification,” Opel Association of North America, 1998-2000, clubs.hemmings. com/clubsites/ oana/tech/GTYears.pdf, accessed 8 April 2012; Stewart Grant, “Opel’s fruit,” Popular Classics September 1990, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 154-159; Dennis Jenkinson, “The Opel GT: A sports 2-seater,” Motor Sport September 1970, reprinted in ibid, pp. 118, 165; David LaChance, “1969-1973 Opel GT: This sporty German two-seater is flying well under collectors’ radar,” Hemmings Motor News January 2009; John Lamm, “Trying to Live with Big Brother,” Motor Trend Vol. 24, No. 3 (April 1972), reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 166-169; Richard M. Langworth, “Crystal Ball: Opel GT,” Automobile Quarterly 1982; Heinrich Lingner, “Zwei Sportcoupés abseits des Mainstream,” MotorKlassik 12 April 2010, www.motor-klassik. de, accessed 8 April 2012; Longrooffan, “Curbside Classic: 1968 Opel GT: Jutta’s Daily Driver,” Curbside Classic, 26 May 2011, www.curbsideclassic. com/ curbside-classics-american/ curbside-classic-1968-opel-gt- juttas-daily-driver/, last accessed 11 April 2012; John Matras, “1970 Opel GT 1.9: Mini-Vette?” Special Interest Autos #159 (May-June 1997), reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 192-199; Gunther Molter, “Opel GT,” Road & Track Vol. 20, No. 4 (December 1968), reprinted in ibid, pp. 20-21; “Motor Road Test No. 24/70: Opel GT: For sporting gents—at a price,” The Motor 20 June 1970, reprinted in ibid, pp. 107- 112; “New Cars for 1970: Opel Kadett and GT,” World Car Guide February 1970, reprinted in ibid, pp. 92-93; Eric Nielssen, “GM’s Gee-Whizzers: Exciting Things from GM’s Brains Abroad,” Car Life December 1967, reprinted in ibid, pp. 6-10; “Opel Experimental GT,” www.medial. com/opel/expgt.htm, accessed 8 April 2012; “Opel GT,” Imported Cars 1971, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 122-126; “Opel GT,” Road Test January 1970, reprinted in ibid, pp. 101-103; “Opel GT,” Road Test January 1971, reprinted in ibid, pp. 132-133; “Opel GT,” NetCarShow, no date, www.netcarshow. com, accessed 8 April 2012; “Opel GT 1.9,” Car and Driver Vol. 15, No. 3 (September 1969), pp. 66-69, 82; “Opel GT: Big Surprise…at your friendly Buick dealers,” Car Life June 1969, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 48-53; “Opel GT: throughout the years,” SYL.com, 1 October 2006, www.syl. com/travel/ opelgtthroughouttheyears.html, accessed 8 April 2012; Opel Motorsport Club, “Opel GT + FAQs,” OpelClub.com, 2008, www.opelclub. com/html/ opel_gt___faqs.html, accessed 8 April 2012; “Opels with Hairs on Their Chests,” CAR May 1971, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 162-163; Herman Pelgrom, “Honey, I Shrunk the ‘Vette: The Opel GT Story,” Motor Authority, 30 May 2010, www.motorauthority. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Sylvia Poggioli, “Marking the French Social Revolution of ’68,” NPR, 13 May 2008, www.npr. org, accessed 22 April 2012; “Road Test: Opel GT: ‘Mini-Brute’ Stage 11,” Motorcade June 1969, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 56-59; L.J.K. Setright, “Opel GT,” CAR August 1970, reprinted in ibid, pp. 104-106; Mike Siegel, Opel GT: Story of a Dreamcar [trailer], Eldorado Film, “OPEL GT – DRIVING THE DREAM out on DVD !” YouTube, https://youtu.be/rXUrGF4-Jio, uploaded 11 December 2008, accessed 8 April 2012; Jerry Sloniger, “3000 Miles and Two ‘Small’ Rallies in an Opel GT,” World Car Guide November 1969, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 84-88, “Opel GT,” Foreign Car Guide February 1969, reprinted in ibid, pp. 22-25 and “Preview Test: Opel GT,” Car and Driver Vol. 14, No. 6 (December 1968), pp. 74-75; Daniel Strohl, “Might Mouse: The diminutive, but sporty, 1969 Opel GT 1.1L,” Hemmings Sports & Exotic Car #7 (March 2006): 20–25; “The history of the development of the Opel CIH engine, 1966-1993,” Customs ‘n Classics, n.d., www.customs-n-classics. dk, accessed 7 April 2012; “The $3500 GT: Comparing the Datsun 240Z, Fiat 124 Sports, Opel GT, MGB GT and Triumph GT6—a closer contest than we expected,” Road & Track Vol. 22, No. 11 (July 1971), reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 136-142; “Three Ways to Approach a GT,” Sports Car Graphic March 1970, reprinted in ibid, pp. 94-100; Jerry Titus, “Corvair Monza GT: Chevy’s Forward-Look Exercise is in the right direction,” Sports Car Graphic August 1963, reprinted in Corvair Performance Portfolio 1959-1969, ed. R.M. Clarke (Cobham, England: Brooklands Books Ltd., ca. 1998), pp. 58-61; “Tuning Test: Opel GT: More power from GM’s German coupe,” CAR May 1971, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 164-165; Bart van Ark, “Manufacturing prices, productivity, and labor costs in five economies,” Monthly Labor Review July 1955, pp. 56-72; Bruno von Rotz, “Opel GT 1100 und 1900 – nur Fliegen war schooner,” Zwischengas. com, 31 October 2011, www.zwischengas. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Glenn Waddington, “Opel Fruit,” Classic Cars August 2000, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 43-47; Sydnie A. Wauson, ed., Opel GT • Kadett • 1900 • Manta 1966-1975 Shop Manual, 5th ed. (Arleta, CA: Clymer Publications, 1986); “Why the Excitement at Buick-Opel Dealers: Opel GT is a new, honest to goodness sports car for highway or race course,” Road Test July 1969, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973, pp. 64-70; “Wklopf,” www.opelgt. com/ forums/general-discussions/ 28343-i-think-im-love-again.html, accessed 8 April 2012; Michael Wood, “Opel-escent,” Your Classic, January 1994, reprinted in ibid, pp. 188-191; the brochure “Opel GT – Das klassicsche Sport-Coupé,” published by Opel in 1998; the Wikipedia® entries for the Bretton Woods system (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bretton_Woods_system, accessed 1 November 2011); Get Smart (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Get_Smart, accessed 1 May 2012); the Isuzu Gemini (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isuzu_Gemini, accessed 7 May 2012); Opel (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel, accessed 8 April 2012), the Opel Rekord Series C (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel_Rekord_Series_C, accessed 20 April 2012), the Opel GT (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel_GT, accessed 7 April 2012), the Opel Kadett (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel_Kadett; accessed 30 April 2012); the Opel Manta (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel_Manta, accessed 27 April 2012); and Opel’s OHV engine (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel_OHV_engine, accessed 30 April 2012); and the German Wikipedia entry for the Opel GT (de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opel_GT, accessed 8 April 2012).

Additional information on competition Opel GTs came from Phillippe Calvet, “Opel GT Greder Sbarro, 1969,” Franco Sbarro: Another vision of car, n.d., sbarro.perso.neuf. fr, accessed 10 April 2012; “Der Steinmetz Opel GT,” Opel GT World, n.d., www.opelgtworld. de, accessed 10 April 2012; “Opel GT Motorsport (1968-1975): Documenting the career of a mighty sports car,” European Car February 2009, www.europeancarweb. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Stefan Örnerdal and Andrew Horrox, “Formula 2 Register: F2, Voiturettes, FJ, F3 and Le Mans Results, 1998-2012,” www.formula2.net, accessed 8 April 2012; Gianni Rogliatti, “The Opel GT Lives!” Automobile Quarterly Vol. 10, No. 1 (1st Quarter 1972), pp. 50-55; Studio Futuro, Conrero Official Site,www.conrero. com, accessed 8 April 2012; and “World Sportscar Championship,” Racing Cars Chassis Numbers & Database Races Results, 2000, wspr-racing. com, accessed 10 April 2012.

Information on the Opel GT/2 came from Syed, “1975 Opel GT2 Concept,” IEDEI, 16 March 2012, iedei.wordpress. com/ 2012/03/16/opel-gt2/, accessed 8 April 2012; “Tomorrow’s Car Today: Opel’s Car for the ’80s,” Asian Auto July 1976, reprinted in Opel GT Ultimate Portfolio 1968-1973), pp. 186-187; and Ron Wakefield, “Opel GT-2: Stylish and economic sports car of tomorrow,” Road & Track Vol. 27, No. 4 (December 1975), reprinted in ibid, pp. 183-185.

Additional details on Opel design and other Opel vehicles of this period came from “Bochum Plant, Facts and Figures,” Opel Media/GM Europe, no date, media.opel. com, accessed 10 April 2012; Bill Bowman, “Corvette 2-Rotor,” Generations of GM, GM Heritage Center, history.gmheritagecenter. com, accessed 27 April 2012; “Brissonneau & Lotz: Historique,” Floride Caravelle Club de France, 2011, fccdf.free. fr, accessed 7 April 2012; “Car and Driver Road Test: Opel Kadett L Station Wagon,” Car and Driver Vol. 13, No. 8 (February 1968), pp. 53-54, 92; Corvette Museum, “2011 Corvette Hall of Fame Clare MacKichan,” YouTube, https://youtu.be/KNkDFmTzUBo, uploaded 17 November 2011, accessed 8 April 2012; David R. Crippen, “Reminiscences of Irwin W. Rybicki,” 27 June 1985 [interview], Automotive Design Oral History Project, Benson Ford Research Center, Accession 1673, www.autolife.umd.umich. edu/Design/ Rybicki_interview.htm [transcript], last accessed 8 April 2012, and “Reminiscences of William L. Mitchell,” August 1984 [interview], Automotive Design Oral History Project, Benson Ford Research Center, Accession 1673, www.autolife.umd.umich. edu/Design/ Mitchell/ mitchellinterview.htm [transcript], last accessed 9 April 2012; “Engine & Drive — Where should they go?” Road & Track Vol. 24, No. 11 (July 1973): 34–41; Mike Fordham, “Friday Car Crush #21: Opel GT/W ‘Geneve'” (28 October 2011, Influx, www.influx. co.uk, accessed 27 April 2012); “Group Test: Ford Capri 2000GT, Opel Manta 1.6S, Vauxhall Firenza 2000, Morris Marina 1.8TC Coupe, Toyota Celica,” The Motor 23 October 1971, pp. 74-79; “Johann ‘Hans’ Christian Mersheimer,” Opel History Wiki, 1 July 2011, www.cokebottle-design. de, accessed 12 April 2012; “Jordan, Charles M.,” Generations of GM History, GM Heritage Center, history.gmheritagecenter. com, accessed 8 April 2012; “Knudsen, Semon E.,” Generations of GM History, GM Heritage Center, history.gmheritagecenter. com, accessed 13 April 2012; Michael Lamm, “Opel Kadgett & Caravan 1000 Road Test,” Motor Trend Vol. 16, No. 4 (April 1964): 42–46; Michael Lamm and David R. Holls, Century of Automotive Style: 100 Years of American Car Design (Stockton, CA: Lamm-Morada Publishing Co. Inc., 1997); “Lapine, Tony,” Generations of GM History, GM Heritage Center, history.gmheritagecenter. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Randy Leffingwell, Corvette: America’s Sports Car (Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1997) and Porsche 911: Perfection By Design (Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 2005), p. 65; Paul Niedermeyer, “Automotive History: How The 1960 Corvair Started A Global Design Revolution,” Curbside Classic, 15 August 2011, www.curbsideclassic. com/automotive-histories/ automotive-history- how-the-1960-corvair- started-a- global-design-revolution/, last accessed 21 April 2012, “Curbside Classic: 1966-1973 Opel Kadett (B) – It Dethroned the Volkswagen,” Curbside Classic, 9 March 2012, www.curbsideclassic. com/ curbside-classics-european/ curbside-classic- 1966-1973-opel-kadett-b- it-dethroned-the-volkswagen/, last accessed 14 April 2012, and “The Story Behind the Best Bob Lutz Photo Ever,” The Truth About Cars, 4 October 2010, www.thetruthaboutcars. com, last accessed 14 April 2012; “Obituary: William L. Mitchell, Auto Executive, 76,” New York Times 15 September 1988, www.nytimes. com, accessed 13 April 2012; “Opel Design: The Story,” GM Europe, 2006, planer-motorshow. gmeuropearchive.info, accessed 8 April 2012; Ken Polsson, “Chronology of Chevrolet Corvettes,” 4 April 2012, kpolsson. com/vettehis/, accessed 18 April 2012; “Rybicki, Irvin W., Generations of GM History, GM Heritage Center, history.gmheritagecenter. com, accessed 21 April 2012; Michael Scarlett, “2 Car Test: Sunbeam Rapier – Opel Manta,” Autocar 10 December 1970, pp. 57-61; Mark Theobald, “Strother MacMinn: A Man of Wit and Genius,” Coachbuilt, 2004, www.coachbuilt. com, accessed 12 April 2012; and Anthony Young and Mike Mueller, Classic Chevy Hot Ones: 1955–1957 2nd ed. (Ann Arbor, MI: Lowe & B. Hould Publishers, 2002).

Background on the Corvair Monza GT came from “2 Magnificent Monzas: General Motors Styling bridges the gap between dream and reality,” Road & Track Vol. 14, No. 12 (August 1963), pp. 16-18; the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, “1962 and 1963 Chevrolet Corvair Concept Cars,” HowStuffWorks.com, 13 November 2007, auto.howstuffworks. com/1962-and-1963- chevrolet-corvair-concept-cars1.htm, accessed 8 April 2012, and “Sweet Dreams: Those Memorable Corvair Specials,” Cars That Never Were: The Prototypes (Skokie, IL: Publications International, 1981), pp. 14-19; Gerry Aubé, “Corvair Design Studies: General Motors’ Experimental Corvairs,” CorvairCorsa.com, n.d., www.corvaircorsa. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Bill Bowman, “1962 Chevrolet Corvair Monza GT Concept,” Generations of GM History, history.gmheritagecenter. com, accessed 8 April 2012; Richard M. Langworth and the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, The Complete Book of Corvette (New York: Beekman House, 1987); Randy Leffingwell and David Newhardt, Mustang: Forty Years (St. Paul, MN: Crestline/MBI Publishing/Barnes & Noble Publishing Inc., 2006); and the Wikipedia entry for the Corvair Monza GT (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corvair_Monza_GT, accessed 8 April 2012).

Some exchange rates for the dollar, the sterling, and the Deutschmark were estimated based on Lawrence H. Officer, “Exchange Rates Between the United States Dollar and Forty-one Currencies,” MeasuringWorth, 2011-2012, https://www.measuringworth.org/exchangeglobal/, used with permission. Exchange rate values cited in the text represent the approximate equivalency of U.S. and British or German currencies at the time, not contemporary U.S. suggested retail prices, which are cited separately. Please note that all exchange rate equivalencies cited in the text are approximate, provided solely for general reference; this is an automotive history, not a treatise on currency trading or the value of money, and nothing in this article should be taken as financial advice of any kind!

RELATED ARTICLES

- A Tale of the Shark and the Rat: The Chevrolet Corvette Stingray (C3)

- Bucking the System: The 1963-1967 Corvette Sting Ray (C2)

- Cheap and Cheerful: The European Ford Capri

- Plan C: The Short-Lived Six-Cylinder MGC and MGC GT

- Contrary Compact: The Life and Death of the Chevrolet Corvair

- The Original Datsun Z-Car

Excellent article which covers all bases of this car’s history.

Great job and keep up the good work guys!

Great article. I always have had a fond desire for the GT. My mom bought a brand new Kadett in 1966. So when the GT showed up, I wanted one. Never got it, but always admired them. Thanks again…

I am rather surprised that nothing was mentioned about the Pontiac Banshee. To me it seemed closer in styling and concept. Though I don’t know that the development of the Banshee had anything to do with the Opel.

I mentioned it in passing in the sidebar (and I discussed the Banshee project at length in the Fiero article), but as far as I know, there’s no direct connection between the two other than their general conceptual resemblance. Bill Mitchell was obviously aware of both of them (and was apparently keen on the idea of a small sports car), but most of what I’ve read about the Banshee suggests that it was driven more by DeLorean than Mitchell.

Still, the Opel and the Pontiac were developed at roughly the same time, and it does raise the question, “Why was Buick selling a small sports car in 1969 when GM had vetoed Pontiac’s attempt to do the same thing five years earlier?” I think the answer has more to do with Buick’s established relationship with Opel than anything else; if Buick had developed the GT in-house, I suspect they would have gotten the same response DeLorean did.

Growing up in germany in my late teens the Opel GT (and the Ford Capri) immediately caught my attention as it brought some drama to a rather uninspired car design scene. Unfortunately my pockets weren’t deep enough to afford one. But during the 1969 IAA in Frankfurt I was invited to the Opel Design Center in Ruesselsheim. I had the good fortune to meet Erhard Schnell who showed me round the less sensitive areas including clay models of the Aero GT and the Opel CD Concept.

Allow me two comments. I am surprised you did not include a picture of the NSU Prinz 4, the absolute best clone of the original Corvair, albeit at miniature scale.

The pictures of the Kadett B coupe show the later LS version not the first coupe version, which to me looked more harmoniuos. Thanx for another great and well researched story

Thanks!

The main reason I included a picture of the Imp, rather than the Prinz 4 or some of the other obvious Corvair scions, was just that I had one handy. The list of cars obviously influenced by the Corvair is lengthy — Paul Niedermeyer over at Curbside Classic did a more exhaustive survey last year.

There are two different Kadett coupes shown: a red one that I *think* is a ’67 (please correct me if I’m wrong) and a 1969 LS fastback coupe. They’re definitely not the same car.

I am afraid that all three Kadett B coupes shown(plus or minus wheeltrim and vinyl roof) are of the "LS" type built between 8/67 – 7/73. The first B coupe had different sheetmetal from the B-pillar rearwards. It was built from 8/65 – 7/70. Here is a picture of it [Wikimedia Commons]

Again thank you for the great work!!!

Thanks for the clarification! Detailed information on workaday Opels of this vintage is a little scarce for those of us who don’t read German, and identifying model years is made more challenging by the disparity between when models were released in Germany and when (or if) they appeared in the U.S.

While my parents lived in Paris during the mid ’60s, they owned a Simca 1000, one of the many Corvair clones. I drove that car to the 1967 Le Mans 24 hrs and watched Foyt and Gurney make it two in a row for Ford.

Thanks for the fantastic story of the Opel GT. The latest in a long line of brilliant, well researched and informative stories about the auto industry and its most interesting products. I always lusted after one of these when I was in high school. Keep the great stuff coming.

I owned two Opel GTs at different times in the late 1970’s. One of them was the actual J. Edgar Opel (!), so I can attest to its still existing in 1977-1978, in upstate New York (Dutchess County).

By the time I had it, it had passed through several hands. The original paint job Car& Driver gave it had been painted over in a not-very-appealing metallic brown. It still had all of its C&D installed modifications, exhaust, etc. The engine was a little tired by the time I had it, compression was down – it had led a “well used” life by every owner flogging it in the spirit of C&D. It was an absolute blast to drive.

Up until then my interests leaned more to American iron – Mustangs and the like were a core part of my automotive formative years. J. Edgar Opel, low compression notwithstanding, opened my eyes to how much fun a great handling ‘European sports car’ could be. At the time it was nothing less than a religious revelation – it would take hard 90 degree turns at 40 mph with barely a trace of body lean. The stock Opel GT I had which came before it was a delightful car, significantly mroe civilized than the MBGs and the like of the time, much more comfortable and practical as a ‘daily driver’ sports car, but J. Edgar Opel was a mystical experience for me.

I traded it for a 1972 Camaro SS396 – mistake. The person I traded it to was going to rebuild the engine and repaint it back to the original C&D colors. I didn’t personally stay in touch with him, but heard through the local grapevine that he wrecked it hooning around one night, which would have been around 1979. The rumor was that a few years later the wrecked car was still in his garage in Kingston NY in the early 1980’s.

I’ve now owned 103 cars in my 38 years of driving, and this is one of the ones I regret selling. I’ve been trolling e-bay and craigslist for years looking for a nice, stock GT.

Hello, I don’t know if you’ve found your dream stock opel gt or not, but I have a 1970 1900 GT that is almost all stock except for things you wont miss like the original solex carb, and Points. it has a weber 32/36. it has electronic ignition and an aluminum radiator. it has an added ignition relay and a modern sony stereo. but the engine,transmission and exhaust are all original, as is the interior. here is a link to my CL post, which will be active until it’s sold. some great pictures. my plan for it was to install a 98 VW TDI engine(minimal computer)using an Acme Adapter and a Toyota 5 speed, but this car is too nice at 44 to go swapping in a non stock engine and the stock engine runs beautifully and sounds so nice it would be kind of a shame. it’s a very exotic looking car for sure.

Aaron,

Thank you for the memories, so to speak.

I was in Munich in the summer of 1970 where I saw a red Opel GT in its natural enviroment on Belgium Block pavement. A fantastic memory. I returned home excited and smitten by the GT. Later in late spring 1971, I learned that the local Buick dealer had a red 1970 1.9Litre CIH GT in stock which had languished at the dealership , I initially believed, because of competition from the Datsun 240Z and Porsche 914. I was able to buy that car with a $500 discount for about $3000. Later I learned that Opel GT’s sold because of enthusiasts like me despite the indifference of Buick and its dealers to the Opel brand. Buick never properly understood the potential of the GT and later the Opel Manta, but we owners did.

Shortly after I bought the Opel GT, I swapped out the stock Goodyear tires for Michelin XAS tires, added a rear anti-roll bar, and Koni shocks–the results were transformative. It was such a fun car to drive both in summer and in winter with snow tires. I also loved watching the headlamps swivel with the forward push of the headlamp lever–because it was a manual system, the headlamps never failed to open and engage, summer or winter.

During the winter there were many great skiiing road trips to Vermont with the GT initially stopping at Smith College in North Hampton to pick up a girl friend on the way usually to Stowe. The GT easily ran at over 100+ on the Interstate with two sets of ski’s on the diminutive ski rack. Driving the GT on Vermont 100 was always great fun. It handled the curves with the pleasure one experienced during a fun mogul run. Wow, was it fun.

The only downside of the GT was the poor rust conditioning/prooofing. By 1976, despite solid mechanics at about 113,000 miles, the tin worm had been very destructive and I unfortunately sold my loved Opel GT for the worst car of my life, my disastrous VW Rabbit–but that is another story for another time.

Thank you for reminding me of all of the great miles and smiles I had with my GT.

Vic

Rust seems to have been an endemic problem with the GT. The GT’s body WAS rust-proofed by Brissonneau et Lotz, but from what I can tell, the design of the body structure appears to have made it particularly susceptible and more challenging to repair once rot (or serious collision damage) does set in.

The Steinmetz kits were available in the US. They were sold and installed by MORE Opel in Seattle. Modified Opels with 125 to 140 BHP gave spirited performance, easily matching the 240Z, but for much more money!

I am trying to restore a 1973 Opel Gt. anyone know a mechanic in Toronto that can help with an engine swap or fixing the original engine?

anyone have an old body they would like to sell?

I had three Opel GT 1969, 1970 had 4 weber carbs fast, 1973 had a automatic was the cleanest and should of kept,

The 1900 engine I fItted a down draft 2300 ford pinto carberator and it fit with a manual choke.

Thank you for the article. I had heard and read of the Corvette connection in a Corvette magazine article and it made passing reference to the link between the Corvair and the GT.

I bought a field-find 1969 GT a couple of years ago sort of as a joke. We’d paint it up as a Compuware Corvette and take it racing in the 24 Hours of LeMons. That was three years ago, and the little car has done well in its 12 or so races plus a trip to Bonneville. It certainly has grown on me, and it has developed a bit of a following in LeMons circles.

To show you how much I have been sucked into the Opel world I am now the editor for the Blitz, the Opel Motorsport Club’s newsletter. I’d love to be able to reprint this article in the Blitz.

BTW, Opel GTs and to some extent the Mata are still well supported. There is a company in California that hoards old parts and when needed has reproduction parts made. The is also a company in Germany that does the same. Prices are very reasonable.

Mike

Mike,

If you’d like to talk about reprinting the article, drop me a line — I’d be happy to discuss it. Thanks!

Aaron,

I happened on this article, and my post above, while researching the J Edgar Opel. I never got your reply. I’d still love to be able to reprint the article.

Hey Mike,

I either missed, forgot, or somehow lost your inquiry. Feel free to send me a message via the contact form and we can discuss it. My apologies — I do try to reply even if the answer isn’t always yes.

I had a neighbour, when I was a boy in the 1970s had a 1971 Opel GT coupe. At the time, I thought it was the ugliest car in the neighbourhood. At the time, I thought the Toyota Corona and Corona Mark II was the best looking car, or the American Chevy Nova. But with time, I found the car more attractive than any of the American cars sold during the 1970s and the 1980s. And certainly better looking than the Toyotas, Datsun/Nissan cars sold during the 1980s.

GREAT article and a great reference for restoring my 1970 GT!

Always loved this car. Mine was a Orange 1972 with white interior. Once on a whim I drove it to find out the best mileage I could get on level roads at 55mph I was able to get 36.2 mpg. The car had 47000 miles on it, all stock. Sold it for what I paid for it in the 70’s. Wish I had never sold it, never saw a better one even the clock ran perfectly.

Great history on the GT! Thanks!

Age 16, I had saved my pennies for 2 years working part time after school and mowing grass on weekends, bought a 2 year old 69 1100cc GT. It was silver with red interior, a great color combo for this car I thought. It was very reliable and ran good even with the small engine, I sold it after 3 yrs for what I paid for it!

Mike,

I took the liberty of editing your email address to make it a little less obvious to spam bots. If you want me to put it back the way it was, I will, but I take no responsibility for any consequences. (I don’t know about you, but I get a lot of spam email as it is!)

Great read, really enjoyed it.

I have a ’74 Manta which has been away from salted roads most of its life, so it didn’t succumb to rust.

As a kid, I remember going to the Buick dealer with my father around 1976-77. At this particular dealer, there was only one Opel sign, way around the back nearly hidden from view. All the European Opels were gone, but there were a couple of Isuzu-built coupes in stock, one which had a turbo. We test drove one while waiting for our car to be serviced and I remember Dad liking it quite a bit. But the salesman told my dad who wasn’t knowledgeable about cars that all Opels are junk.

It’s amazing that Opel was able to sell any cars in the U.S. given Buick’s indifference to the brand

I have to wonder if some of that indifference was defensive, especially after the demise of the Bretton Woods system started making the German-built cars more expensive. It may just have been a matter of smaller dealer margins, of course — a salesman is almost always going to try to talk you into a car on which he makes $200 over one on which he only makes $100.

Although Chuck Jordan’s contributions came late in the development of the Opel GT he needs to be recognized for what he did with the rest of the Opel line during his time there. He led Opel from being the “farmer car” with lackluster design to a market leader in a very short period of time. He also turned the Opel Design studio into a “hot” place that designers wanted to be part of.

The article mentions the Manta and Rekord. Also, one should look at the Ascona. The original Opel CD may have been a fantasy image car but it really demonstrated the creativity that Opel could be capable of.

To put an aspect of this into perspective, Chuck was the #2 to Bill Mitchell and had been for a while when he went to Germany. He went to Opel not just as a directed posting but as a place where he knew he could make a turnaround that all the executive suite at GM could not avoid recognizing. The cars he created were far superior in looks, they had cast off the “farmer car” stigma and delivered increased sales.